2. Language Models#

2.1. Motivation#

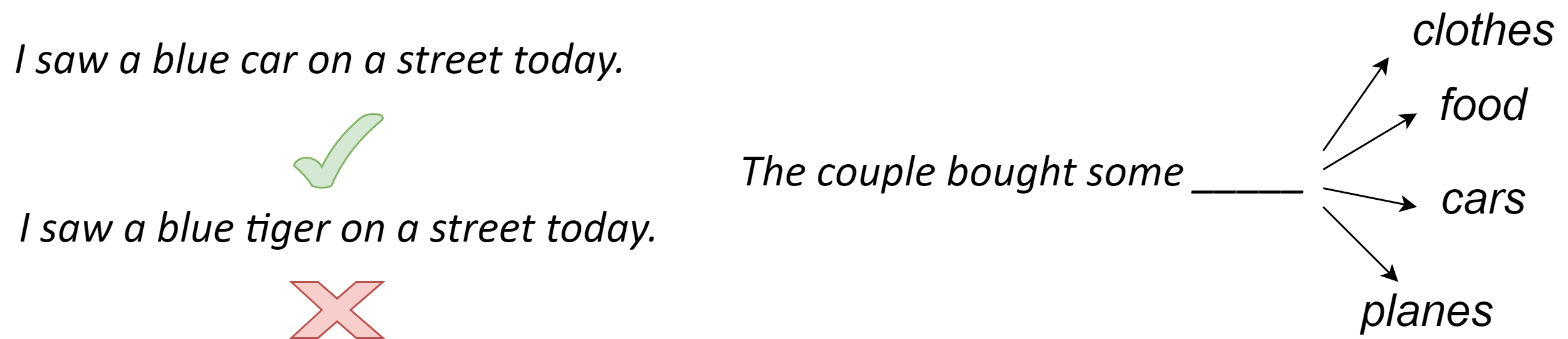

Natural languages emerge from formal or casual communications between human beings and only have a limited set of formal rules to follow. Linguists have been directing decades’ efforts to modeling languages via grammars, rules, and structure of natural language. In NLP, language modeling [Gol17] tasks involve the the use of various statistical and probabilistic techniques to determine the probability of a given sequence of words forming a sentence that make sense [Fig. 2.1].

Fig. 2.1 Illustrating basic language modeling tasks: assigning probability to a sentence (left); and predict the next word based on preceding context (right).#

Language modeling is an indispensable components in real-world applications. A language model can be used directly to generate new sequences of text that appear to have come from the corpus. For example, an AI-writer can generate an article with given key words. Moreover, language models are an integral part of many text-related applications, where they ensure output word sequences in these tasks to have a sensible meaning or to appear fluent like genuine human languages. These tasks include

Optical character Recognition, a task converting images to sentences.

Machine translation, where one sentence from one language is translated to a sentence in another language.

Image captioning, where a image is used as the input and the output is a descriptive sentence.

Text summarization, where a large paragraph or a full article is converted several summarizing sentences.

Speech recognition, where audio signal is converted to meaningful words, phases, and sentences.

A closed related language modeling task is predict the next word following a sequence of words.

Predicting the next word in a language system can be much more challenging than predicting the next observation in the many physical system. One perspective is that the evolution of many physical systems can governed by physical laws that are well established; on the other hand, the generation of next word, sentence, and even logically coherent paragraph is closely related to human reasoning and intelligence, which remain poorly understood. In fact, it is widely believed that being able to write up logical and coherent paragraphs is an indication of human-level intelligence [RWC+19].

In this section, we first consider a classical \(n\)-gram statistical language approach [MSchutze99], where we count the co-occurrence of words and model the language generation using probabilistic models (e.g., Markov chains). \(n\)-gram models focus on predicting next word based on the superficial co-occurrence counts instead of high-level semantic links between the context and the unknown next word, It further suffers from the curse of dimensionality since sentences are normally long and language vocabulary size is huge (e.g., \(10^6\)). Over the past two decades, the neural network based language models have attracted considerable attention because these models are able to reveal deep connections between words as well as to alleviate the dimensionality challenge. Our focus in this section is on early development of neural language models; recent developments of pre-trained language models (e.g., GPT 1-3 [BMR+20, RNSS18, RWC+19]) will be covered in next section.

2.2. Statistical Language Models#

2.2.1. \(n\)-gram Language Model#

The essential goal of language model is to estimate the joint probability of word sequence \(w_{1:N} = w_1,...,w_{N}\). By definition, the unbiased probability estimation is given by

Estimating the probability has the following challenge:

Given a vocabulary size \(V\), the number of events \(w_{1:N}\) is exponentially increasing with \(N\). As \(N\) can take arbitrarily large value, it would not be possible even to store the model.

Because of the intractably large number of events, getting reliable estimation of the denominator and the nominator requires impractically large data.

Alternatively, one can achieve the joint probability estimation via a truncated conditional probability framework. To begin with, the joint probability the sequence \(w_{1:N}\) has the following decomposition based on the conditional probability chain rule:

The language modeling task involves the estimation \(P\left(w_1,...,w_N\right)\). The task is equivalent to estimate the conditional probability of predicting \(w_N\) based on \(w_1,...,w_{N-1}\) thanks to

In the truncated-\(n\) conditional probability framework, we approximate \(P(w_{1:N})\) via

The truncated-\(n\) conditional probability framework is formally known as \(n\)-gram statistical language model. The \(n\)-gram statistical language model is one fundamental model that estimates probabilities by counting the co-occurrence of \(n\) consecutive words. More precisely, an \(n\)-gram is a sequence consisting of \(n\) words. For example, given a sentence The homework is due tomorrow, it has:

2-grams (or bigrams) like the homework, homework is, is due, due tomorrow;

3-grams (or trigrams) like the homework is, homework is due, is due tomorrow;

4-grams like the homework is due, homework is due tomorrow.

Often we pad the sequence in the front by \(n-1\)

For example, in the bigram language model, we have

and therefore

2.2.2. Model Parameter Estimation#

For a \(n\)-gram language model, there are \(|V|^n\) the model parameters to be estimated:

Here \(|V|\) is the vocabulary size.

Given a training corpus, the MLE (maximum likelihood estimator) of \(n\)-gram conditional probability used above can be simply obtained by counting. Specifically, for a bigram model, we have

where \(\operatorname{count}(x, y)\) is the total count of bigrams \(x,y\) in the corpus and \(\sum_{w} \operatorname{count}\left(w_{n-1}, w\right)\) is the count of all bigrams starting with \(w_{n-1}\).

For a trigram model, we have

For example,

2.2.2.1. \(\star\) Deriving The MLE#

Consider a sequence of random variables \(w_0, w_1, ...,w_N\) representing a sentence composed of a sequence of tokens taken from the vocabulary \(|V|\). Let \(w_0\) be deterministic and take the value of starting token

To estimate the model parameter, we look at the log likelihood of a sample sequence \(w_0, w_1,...,w_N\), which is is given by

Here \(\operatorname{count}(i, j)\) is the count of bigram \(i,j\) in the training corpus.

Because \(\theta_{ij}\) is under additional constraints given by

we can use Lagrange multiplier to maximize the log likelihood under constraints. The Lagrange is given by

Set \(\partial L / \partial \theta_{ij} = 0\), we get

One can easily show that $\(\lambda_i = \sum_{j\in |V|} \operatorname{count}(i, j) = \operatorname{count}(i),\)$ therefore,

2.2.2.2. Special case: unigram language model#

In the unigram language model, we assume

We can empirically estimate

where \(\operatorname{count}(w_i)\) is the number of \(w_i\) in the corpus, \(|V|\) is the vocabulary size, and \(N_{|V|}\) is the total number of words in the corpus.

A unigram language model does not capture any transitional relationship between words. When we use a unigram language model to generate sentences, the resulted sentences would mostly consist of high-frequent words and thus hardly make sense.

2.2.3. Choices Of \(n\) and Bias-variance Trade-off#

For a \(n\)-gram model, when \(n\) is too small, say a bigram model, the model can capture synactic structure in the language but can hardly capture the sequential, long distance relationship among words. For example, the syntatic structure like the fact that a noun or an adjective comes after enjoy and the fact that a verb in its original form typically comes after to. For long-range dependency, consider the following sentences:

Gorillas always like to groom their friends.

The computer that’s on the 3rd floor of our office building crashed.

In each example, the words written in bold depend on each other: the likelihood of their depends on knowing that gorillas is plural, and the likelihood of crashed depends on knowing that the subject is a computer. If the \(n\)-grams are not big enough to capture this context, then the resulting language model would offer probabilities that are too low for these sentences, and too high for sentences that fail basic linguistic tests like number agreement.

Typically, the longer the context we condition on in predicting the next word, the more coherent the sentences. But a language model with a large \(n\) can overfit to small-sized training corpus as it tends to memorize specific long sequence patterns in the training corpus and to give zero probabilities to those unseen. Specifically, a \(n\)-gram model has model parameter scales like \(O(V^n)\), where \(V\) is the vocabulary size.

The choice of appropriate \(n\) is related to bias-variance trade-off. A small \(n\)-gram size introduces high bias, and a large \(n\)-gram size introduces high variance. Since human language is full of long-range dependencies, in practice, we tend to keep \(n\) large and at the same time use smoothing tricks, as some sort of bias, to achieve low-variance estimates of the model parameters.

2.2.4. Out Of Vocabulary (OOV) Words and Rare Words#

Some early speech and language applications might just involve a closed vocabulary, in which the vocabulary is known in advance and the runtime test set will contain words from the vocabulary. Modern natural language application typically involves an open vocabulary in which out of vocabulary words can occur. For those cases, which can simply add a pseudo-word UNK, and treat all the OOV words as the UNK.

In applications where we don’t have a prior vocabulary in advance and need to create one from corpus, we can limit the size of vocabulary by replacing low-frequency rare words by

Note that how the vocabulary is constructed and how we map rare words to UNK affects how we evaluate the quality of language model using likelihood based metrics (e.g., perplexity). For example, a language model can achieve artificially low perplexity by choosing a small vocabulary and assigning many words to the unknown word.

2.3. Smoothing and Discounting Techniques#

2.3.1. Add \(\alpha\) Smoothing and Discounting#

One fundamental limit of the baseline counting method is the zero probability assigned to \(n\)-grams that do not appear in the training corpus. This has a significant impact when we use the model to score a sentence. For example, one zero probability of any unseen bigram \(w_{i-1},w_i\) will cause the probability of the sequence \(w_1,...,w_i,...,w_n\) to be zero.

Example 2.1

Suppose in the training corpus we have only seen following phrases starting with denied: denied the allegations, denied the speculation, denied the rumors, denied the report. Now suppose a sentence in the test set has the phrase denied the offer. Our model will incorrectly estimate that the probability of the sentence is 0, which is obviously not true.

A simply remedy is to add \(\alpha\) imaginary counts to all the n-gram that can be constructed from the vocabulary, on top of the actual counts observed in the corpus.

When \(\alpha=1\), this is called Laplace smoothing; when \(\alpha=0.5\), this is called Jeffreys-Perks law.

Take bigram language model as an example, the resulting estimation is given by

Here in the numerator, we add \(\alpha\) imaginary counts to the actual counts. In the denomerator, we add \(|V|\alpha\) to ensure that the probabilities are properly normalized, where \(|V|\) is the vocabulary size. Note that it is possible that \(\operatorname{count}(w_{n-1}) = 0\). We also have \(\operatorname{count}(w_{n-1}, w_n) = 0\) and \(P_{\text{Add-}\alpha}^{*}\left(w_{n} | w_{n-1}\right) = 1/|V|\).

Similarly, for a trigram language model, we have

When \(\operatorname{count}\left(w_{n-2}, w_{n-1}\right) = 0\), we have \(P_{\text{Add-}\alpha}^{*}\left(w_{n} | w_{n-1}, w_{n-2}\right) = 1/|V|.\)

To better understand the bias introduced from adding \(\alpha\) imaginary counts, we can compute the effective count of an event. Let \(c_i\) is the count of event \(i\). Let \(M=\sum_{i=1}^E c_i\) be the total counts of all possible events E in the corpus. The effective count for event \(i\) is given by:

Note that the effective counts defined this way ensures that total count \(M\) satisfies \(\sum_{i=1}^E c_i^*=\sum_{i=1}^E c_i=M\) and the probability of the event \(i\) is \(c_i^*/\sum_i c_i^* = c_i/M\).

In general, if \(c_i > 0\), then \(c_i* < c_i\); if \(c_i = 0\), then \(c_i^* > c_i = 0\). Therefore, when we are adding imaginary counts to all the events, the effective counts of all observed events are decreased and the effective counts for all unobserved events are increased. From the probability mass perspective, add-\(\alpha\) smoothing is equivalent to remove some probability mass from observed events and re-distribute the collected probability mass to all unobserved events.

We can also use the concept of discounting to reflect the change between \(c^*_i\) and \(c_i\). The discount for each \(\mathrm{n}\)-gram is then computed as,

A related definition is absolute discounting, which is given by \(d_i = c_i - c_i^*\).

The bias we add to the n-gram model is reflected on the value of \(d_i\). When \(\alpha = 0, d_i = 1.0\), there is no bias in the n-gram model estimation. For non-zero \(\alpha\), \(d_i < 1\). The smaller the \(d_i\), the large the bias we introduce. For example, when the vocabulary size \(|V|\) is large, but the total number of tokens \(M\) is small, \(d_i\) approaches zero and the bias is thus large.

Example 2.2

Consider following 7 events with a total count of 20. The following table demonstrates the effects of adding 1 smoothing.

event |

counts |

new counts |

effective counts |

unsmoothed probability |

smoothed probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

\(c_0\) |

8 |

9 |

6.67 |

0.4 |

0.33 |

\(c_1\) |

5 |

6 |

4.44 |

0.25 |

0.22 |

\(c_2\) |

4 |

5 |

3.70 |

0.2 |

0.19 |

\(c_3\) |

2 |

3 |

2.22 |

0.1 |

0.11 |

\(c_4\) |

1 |

2 |

1.48 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

\(c_5\) |

0 |

1 |

0.74 |

0 |

0.04 |

\(c_6\) |

0 |

1 |

0.74 |

0 |

0.04 |

2.3.2. Katz’s Back-off#

The smoothing method discussed above borrows probability mass from observed \(n\)-grams and redistributes it to all \(n-\)grams, including both observed ones and unobserved ones. The borrowed amount is controlled by the parameter \(\alpha\). A variation of such re-distribution is to just redistribute the borrowed probablity mass to those unobserved one. A key characteristic of these redistribution methods is that redistribution is carried out equally.

Another popular smoothing approach is back-off. The key idea is that the redistribution of the probability mass to an unobserved \(n\)-gram is dependent on the statistics of its constituent \(n-1\) gram. The latest development of \(n\)-gram language modeling is to use modified Kneser Ney smoothing [CG99].

In the \(n\)-gram Katz’s backoff model,

Here the quantity \(\beta\) is the left-over probability mass for the \((n-1)\)-gram given by:

Then the back-off redistribution weight, \(\lambda\), is computed as follows:

We can interpret the back-off formula in the following way

\(\beta\) is the amount of probability mass that has been borrowed from non-zero events.

\(\lambda\) specifies how the borrowed weight should be re-distributed into zero event, and \(\lambda\) is proportional to the \(n-1\)-gram conditional probability

In the simple case of backing off from bigrams to unigrams, the bigram probabilities are,

Remark 2.1 (Practical simple back-off)

So far we have discussed the back-off idea of redistributing probability mass to unobserved n-grams based on their corresponding lower-order grams. All probabilities will be re-normalized after redistribution. In the practical applications, there are even simpler back-off strategy by satisfying some degree of accuracy. Consider a trigram language model.

If we have trigram probability, use it;

If we don’t have trigram probability, use its bigram probabilities;

if we don’t even have bigram probabilities, then use unigram probabilities.

2.4. Model Evaluation#

2.4.1. Evaluation Metrics#

Given a training corpus, we can build different language models with different \(n\)-gram settings as well as other model smoothing hyperparameter. There model training hyperparameters give different bias and variance trade-off and we need an evaluation method to gauge which hyperparameter is better for intended applications.

One principled way is to evaluate the model predicted likelihood on an unseen test set, which consist of natural language sentences, from the intended applications. with unseen sentences and then compare the probability or its variant computed from different candidate models on the test set. A language model that assigns a higher probability to the test set is considered a better one. We define perplexity of a language model on a test set as the inverse probability of the test set, normalized by the number of words. For a test set \(W = (w_{1} w_{2} \ldots w_{N})\) (\(N\) can be millions),

where \(P\left(w_{1} w_{2} \ldots w_{N}\right)\) can be estimated in an \(n\)-gram model via

Intuitively, perplexity is roughly the inverse probability of the test set. Therefore, a good larnguage model will assign high probability to the test set and produce a low perplexity value. Since \(\ln P(w_{1:N}) \le 0\), the perplexity is always greater than or equal to 1.0. Since the longer the sentence, the more negative \(\ln P\) tends to be, the normalization by sentence length \(N\) reduces such impact.

Remark 2.2 (Caveats)

To compare the performance of two different language models, it is necessary to **keep the vocabulary and the actual word to special token mapping the same. **

Suppose we construct the vocabulary by mapping words whose frequencies are below certain threshold to the

In the inference stage, rare words in the test corpus will be mapped to the

2.4.2. More On Perplexity#

A state-of-the-art language model typically can achieve perplexity value ranging from 20 to 200 on a general test set. How do we interpret the perplexity value? Perplexity can be thought of as the effective vocabulary size under the model, that is, given the context, the number of possible options for the next word.

Some intuition behind such interpretation of perplexity is as follows. Say we have a vocabulary \(\mathcal{V}\) whose size is \(V\), and a trigram model simply predicts a uniform distribution given by

for all \(u, v, w\). In this case, it can be shown that the perplexity is equal to \(V\).

If, for example, the perplexity of the model is 120 (even though the vocabulary size is say 10,000), then this is roughly equivalent to having an effective vocabulary size of 120 for the next word given the context.

Remark 2.3 (Relationship to Cross Entropy)

Given a test set \(W\), we can also write

where \(CE(P_{true}, P)\) is the cross-entropy of the true distribution \(P_{true}\) and our estimate \(P\), given by

This means that, training a language model over well-written sentences means we are maximizing the normalized sentence probabilities given by the language model, which is more or less equivalent to minimizing the cross entropy loss of the model predicted distribution and the distribution of well-written sentences.

We know that cross-entorpy loss is at its minimal when the two distributions are exactly matched.

2.4.3. Benchmarking#

2.4.3.1. Datasets#

The Penn Tree Bank (PTB) [Mar94] dataset is an early dataset for training and evaluating language model. The Penn Tree Bank dataset is made of articles from the Wall Street Journal, contains around \(929 \mathrm{k}\) training tokens, and has a vocabulary size of \(10 \mathrm{k}\).

In the Penn Tree Bank dataset, words were lower-cased, numbers were replaced with N, newlines were replaced with

No |

Sentence |

|---|---|

1 |

aer banknote berlitz calloway centrust cluett fromstein gitano guterman hydro-quebec ipo kia |

2 |

memotec mlx nahb punts rake regatta rubens sim snack-food ssangyong swapo wachter |

3 |

pierre |

4 |

mr. |

5 |

rudolph |

6 |

nonexecutive director of this british industrial conglomerate |

While the processed version of the PTB above has been frequently used for language modeling, it has many limitations. The tokens in PTB are all lower case, stripped of any punctuation, and limited to a vocabulary of only \(10 \mathrm{k}\) words. These limitations mean that the PTB is unrealistic for real language use, especially when far larger vocabularies with many rare words are involved.

Given that accurately predicting rare words, such as named entities, is an important task for many applications, the lack of a long tail for the vocabulary is problematic.

The wikitext 2 dataset is derived from Wikipedia articles, contains \(2 \mathrm{M}\) training tokens and has a vocabulary size of \(33 \mathrm{k}\). These datasets contain non-shuffled documents, therefore requiring models to capture inter-sentences dependencies to perform well.

Compared to the preprocessed version of Penn Treebank (PTB), WikiText-2 is over 2 times larger and WikiText-103 is over 110 times larger. The WikiText dataset also features a far larger vocabulary and retains the original case, punctuation and numbers - all of which are removed in PTB. As it is composed of full articles, the dataset is well suited for models that can take advantage of long term dependencies.

In comparison to the Mikolov processed version of the Penn Treebank (PTB), the WikiText datasets are larger. WikiText-2 aims to be of a similar size to the PTB while WikiText-103 contains all articles extracted from Wikipedia. The WikiText datasets also retain numbers (as opposed to replacing them with N), case (as opposed to all text being lowercased), and punctuation (as opposed to stripping them out).

Metric |

Train |

Valid |

Test |

|---|---|---|---|

Articles |

- |

- |

- |

Number of tokens |

887,521 |

70,390 |

78,669 |

Vocabulary size |

10,000 |

||

OOV ratio |

4.8% |

Metric |

Train |

Valid |

Test |

|---|---|---|---|

Articles |

600 |

60 |

60 |

Number of tokens |

2,088,628 |

217,646 |

245,569 |

Vocabulary size |

33,278 |

||

OOV ratio |

2.6% |

Metric |

Train |

Valid |

Test |

|---|---|---|---|

Articles |

28,475 |

60 |

60 |

Number of tokens |

103,227,021 |

217,646 |

245,569 |

Vocabulary size |

267,735 |

||

OOV ratio |

0.4% |

2.5. Bibliography#

Tom Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared D Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, and et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33:1877–1901, 2020.

Stanley F Chen and Joshua Goodman. An empirical study of smoothing techniques for language modeling. Computer Speech & Language, 13(4):359–394, 1999.

Yoav Goldberg. Neural network methods for natural language processing. Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies, 10(1):1–309, 2017.

Christopher D Manning and Hinrich Schütze. Foundations of statistical natural language processing. MIT press, 1999.

Mary Ann Marcinkiewicz. Building a large annotated corpus of english: the penn treebank. Using Large Corpora, 1994.

Alec Radford, Karthik Narasimhan, Tim Salimans, and Ilya Sutskever. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. URL https://s3-us-west-2. amazonaws. com/openai-assets/researchcovers/languageunsupervised/language understanding paper. pdf, 2018.