25. Application of LLM in IR (WIP)#

25.1. Query Understanding & Optimization#

A Survey of Query Optimization in Large Language Models

Query Rewriting for Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models

25.1.1. Query Categorization#

25.1.1.1. Natural Language Queries#

Question Type |

Description |

|---|---|

Fact-based |

Questions that seek specific facts or information. |

Multi-hop |

Questions that require reasoning over multiple pieces of information or relationships. |

Numerical |

Questions that involve numerical values or calculations. |

Tabular |

Questions that relate to data presented in tables. |

Temporal |

Questions that involve time-related information or events. |

Multi-constraint |

Questions that involve multiple constraints or conditions. |

Examples

Question Type |

Query Examples |

|---|---|

Fact-based |

What is the capital of France? |

Multi-hop |

Who is the CEO of the company that manufactures the iPhone? |

Numerical |

What is the average temperature in July in London? |

Tabular |

Which country has the highest population density? |

Temporal |

When did World War II end? |

Multi-constraint |

Find a hotel in Paris that has a swimming pool and is within walking distance of the Eiffel Tower. |

25.1.2. Query Optimization Overview#

Query Expansion - aims to capture a wider range of relevant information and potentially uncover connections that may not have been apparent in the query.This process involves analyzing the initial query, identifying key concepts, and incorporating related terms, synonyms, or associated ideas to form a new query for creating a more comprehensive search.

Query Decomposition - aims to effectively break down complex, multihop queries into simpler, more manageable subqueries or tasks. This approach involves dissecting a query that requires facts from multiple sources or steps into smaller, more direct queries that can be answered individually.

Query Disambiguation - aims to identify and eliminate ambiguity in complex queries, ensuring they are unequivocal. This involves pinpointing elements of the query that could be interpreted in multiple ways and refining the query to ensure a single, precise interpretation.

Query Abstraction - aims to provide a broader perspective on the fact need, potentially leading to more diverse and comprehensive results. This involves identifying and distilling the fundamental intent and core conceptual elements of the query, then creating a higher-level representation that captures the essential meaning while removing specific details.

25.1.3. GEFEED (Retrieval Feedback)#

When using LLM to optimize query and retrievel processes, there has been efforts on using LLM to generate relevent context for the query [WYW23, YIW+22] based on the internal knowledge of LLM. These relevant context can be used to further refine the query or the retrievel process. However, there are several fundamental drawback in this approach when it comes to knowledge intensive tasks.

LLM has a tendency to hallucinate content, generating information not grounded by world knowledge, leading to untrustworthy outputs and a diminished capacity to provide accurate information.

The quality and scope of the internal knowledge of LLM may be incomplete or out-of-date due to the reliability of the sources in the pre-training corpus. Moreover, due to model capacity limitation, LLMs cannot memorize all world information, particularly the long tail of knowledge from their training corpus [KDR+23].

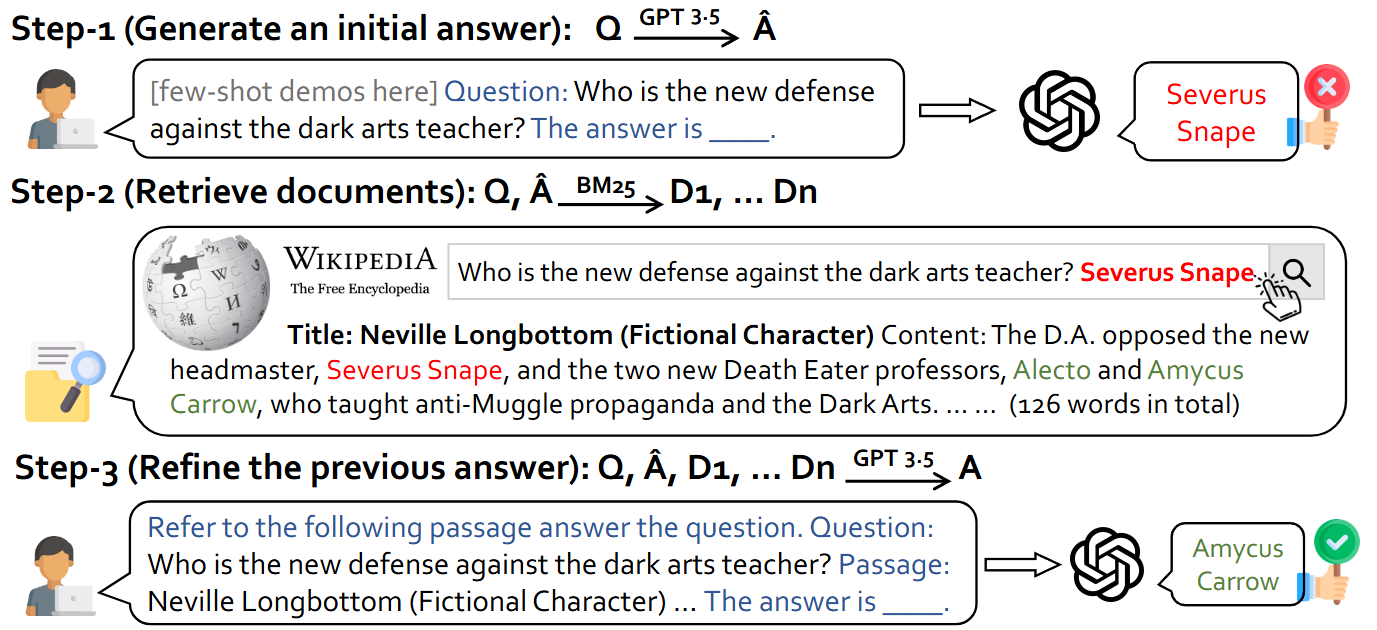

The key steps in GEFEED [Fig. 25.1] are:

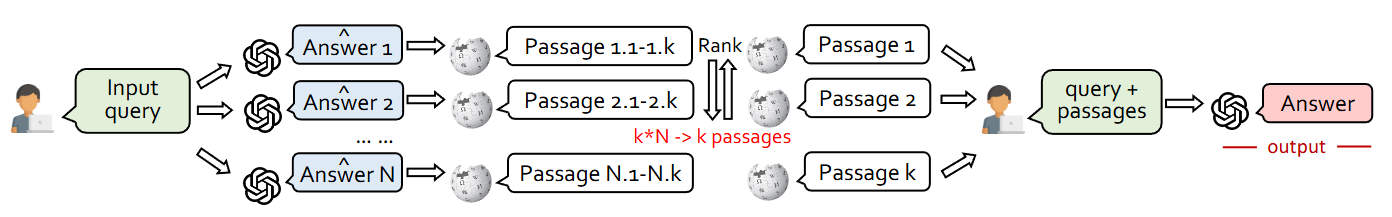

Given a query, the language model generates initial outputs (more than one)[Fig. 25.2].

A retrieval module retrieve expanded relevant information using the original query and generated outputs as a new query.

The language model reader produce the final output based on the expanded retrieved information.

The potential benefits from GEFEED are:

By directly generating the expected answer, rather than performing query paraphrasing, the lack of lexical or semantic overlap with the question and the document can be reduced.

As more relevant documents are retrieved from the corpus using expected answers, the recall and the precision of the retrieved documents can be both improved.

Fig. 25.1 REFEED operates by initially prompting a large language model to generate an answer in response to a given query, followed by the retrieval of documents from extensive document collections. Subsequently, the pipeline refines the initial answer by incorporating the information gleaned from the retrieved documents. Image from [YZL+23].#

Fig. 25.2 The language model is prompted to sample multiple answers, allowing for a more comprehensive retrieval feedback based on different answers. Image from [YZL+23].#

25.2. Query-Doc Ranking#

Is ChatGPT Good at Search? Investigating Large Language Models as Re-Ranking Agents

A Setwise Approach for Effective and Highly Efficient Zero-shot Ranking with Large Language Models

Zero-Shot Listwise Document Reranking with a Large Language Model

25.2.1. Ranking via Query Likelihood#

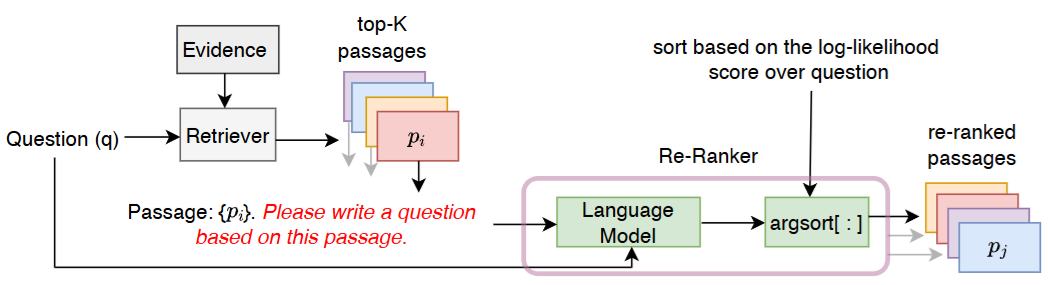

Fig. 25.3 Illustration of using query likelihood to approximate the query doc relevance. Image from [SLJ+22].#

Given a passage \(d_i\) and a query \(q\), the relevance score is approximated by the likelihood of the \(q\) conditioned on \(d_i\) plus an instruction prompt \(\mathbb{P}\).

Specifically, we can estimate \(\log p\left(q \mid {d}_i, \mathbb{P}\right)\) using a LLM to compute the average conditional loglikelihood of the query tokens:

where \(|q| = t\) denotes the number of query tokens. The instruction prompt is given by Please write a question based on this passage to the passage tokens as shown in Fig. 25.3.

[DZD+23] further extends the above query-likelihood approach by including demonstrations. Specificially, let \(z_1,...,z_k\) be positive query-document pair as demonstrations, then the modified query likelihood becomes

The authors found that

Selecting demonstrations based on semantic similarity is not necessarily providing the best value;

Instead, one can use difficulty-based selection to find challenging demonstrations to include in the prompt. We estimate difficulty using demonstration query likelihood (DQL):

then select the demonstrations with the lowest DQL. Intuitively, this should find hard samples that potentially correspond to large gradients had we directly trained the model instead of prompting.

25.2.2. Ranking via Relevance Label Likelihood#

Fig. 25.4 Illustration of using relevance likelihood to approximate the query doc relevance. One can use different rating class and scale to improve the results. Image from [ZQH+23].#

Authors in [ZQH+23] proposed that one can use LLM as zero-shot text ranker by prompting LLM to provide rating for a given query and doc pair. Example rating scale or class include

Binary class: {Yes, No}

Fine-grained relevance label: {Highly Relevant, Somewhat Relevant, Highly Relevant, Perfectly Relevant}

Rating scale: {0, 1, 2, 3, 4}

We can obtain the log-likelihood of the LLM generating each relevance label:

where \(l_k\) is the relevance class label.

Once we obtain the log-likelihood of each relevance label, we can derive the ranking scores.

Expected relevance values: First, we need to assign a series of relevance values \(\left[y_0, ..., y_k\right]\) to all the relevance labels \(\left[l_0, ..., l_k\right]\), where \(y_k \in \mathbb{R}\). Then we can calculate the expected relevance value by:

Peak relevance likelihood: We can further simplify ranking score by only using the loglikelihood of the peak relevance label (e.g., Perfectly Relevant in this example). More formally, let \(l_{k^*}\) denote the relevance label with the highest relevance. We can simply rank the documents by:

The key findings are:

By using more fine grained relevance label will generally improve the zero-shot ranking performance.

It is hypothesized that the inclusion of fine-grained relevance labels in the prompt may guide LLMs to better differentiate documents, especially those ranked at the top.

25.2.3. Pairwise and Groupwise Text Ranking#

Fig. 25.5 An illustration of pairwise ranking prompting. The scores in scoring mode represent the log-likelihood of the model generating the target text given the prompt. Image from [QJH+23].#

Using LLM for pointwise ranking via query or relevance class likelihood has shown good performance, but the success is mainly limited to large-scale models. The hypothesis is that pointwise ranking requires LLM to output calibrated predictions, which can be challenging for less-competent small-scale models. Authors from [QJH+23] proposed that one can leverage pairwise ranking to reduce the difficulity of the task.

As shown in Fig. 25.5, the pairwise ranking paradigm takes one query and a pair of documents as the input and output the comparison result. This potentially resolves the calibration issue.

One can further consider group-wise ranking by prompting LLM to order the relevance of \(k\) candidate passages, as shown in Fig. 25.6.

Fig. 25.6 Illustration of groupwise_ranking for \(k\) passages. Image from [SYM+23].#

With the local order established by either pairwise ranking or groupwise ranking, one can achieve global ordered rank list using a sliding window approach [Fig. 25.7].

Fig. 25.7 Illustration of re-ranking 8 passages using sliding windows with a window size of 4 and a step size of 2. The blue color represents the first two windows, while the yellow color represents the last window. The sliding windows are applied in back-to-first order. Image from [SYM+23].#

25.2.4. Ranker Distillation#

Pairwise distillation: Suppose we have a query \(q\) and \(D\) candidate documents \(\left(d_1, \ldots, d_M\right)\) for ranking. Let the LLM-based ranking results of the \(D\) documents be \(R=\left(r_1, \ldots, r_M\right)\) (e.g, \(r_i=3\) means \(d_i\) ranks third among the candidates).

Let \(s_i=f_\theta\left(q, d_i\right)\) be the student model’s relevance prediction score between \(\left(q, d_i\right)\).

We can use pairwise Ranking loss to optimize the student model, which is given by

25.3. Application in RAG#

25.4. Generative SERP#

25.5. Collections#

Awesome Information Retrieval in the Age of Large Language Model

25.6. Bibliography#

Andrew Drozdov, Honglei Zhuang, Zhuyun Dai, Zhen Qin, Razieh Rahimi, Xuanhui Wang, Dana Alon, Mohit Iyyer, Andrew McCallum, Donald Metzler, and others. Parade: passage ranking using demonstrations with llms. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, 14242–14252. 2023.

Nikhil Kandpal, Haikang Deng, Adam Roberts, Eric Wallace, and Colin Raffel. Large language models struggle to learn long-tail knowledge. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 15696–15707. PMLR, 2023.

Zhen Qin, Rolf Jagerman, Kai Hui, Honglei Zhuang, Junru Wu, Le Yan, Jiaming Shen, Tianqi Liu, Jialu Liu, Donald Metzler, and others. Large language models are effective text rankers with pairwise ranking prompting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.17563, 2023.

Devendra Singh Sachan, Mike Lewis, Mandar Joshi, Armen Aghajanyan, Wen-tau Yih, Joelle Pineau, and Luke Zettlemoyer. Improving passage retrieval with zero-shot question generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.07496, 2022.

Weiwei Sun, Lingyong Yan, Xinyu Ma, Shuaiqiang Wang, Pengjie Ren, Zhumin Chen, Dawei Yin, and Zhaochun Ren. Is chatgpt good at search? investigating large language models as re-ranking agents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.09542, 2023.

Liang Wang, Nan Yang, and Furu Wei. Query2doc: query expansion with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.07678, 2023.

Wenhao Yu, Dan Iter, Shuohang Wang, Yichong Xu, Mingxuan Ju, Soumya Sanyal, Chenguang Zhu, Michael Zeng, and Meng Jiang. Generate rather than retrieve: large language models are strong context generators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.10063, 2022.