26. RAG#

26.1. Motivation#

LLMs have revolutionized natural language processing, but they still face several significant challenges, particularly in knowledge intensive tasks:

Hallucination: LLMs can generate plausible-sounding but factually incorrect information when they are prompted with rare or ambiguous queries, e.g., what is kuula? (a fishing god). And there lacks an intrinsic way of detecting when LLM is making up facts.

Outdated and publically-sourced knowledge: The knowledge of off-the-shelf LLMs is usually limited to their publically-sourced pre-training data, which can quickly become obsolete. LLM cannot answer questions like stock market values, weather forecast, news, etc. that require access to dynamic, ever-changing knowledge; neither can LLM answer questions related to private company documents not used in training data.

Untraceable reasoning: The decision-making process of LLMs is often unclear, making it difficult to verify or understand their outputs.

Expensive cost to inject knowledge: Although one can inject domain knowledge or updated knowledge via continuous pretraining or finetining, the cost of data collections and training is very high.

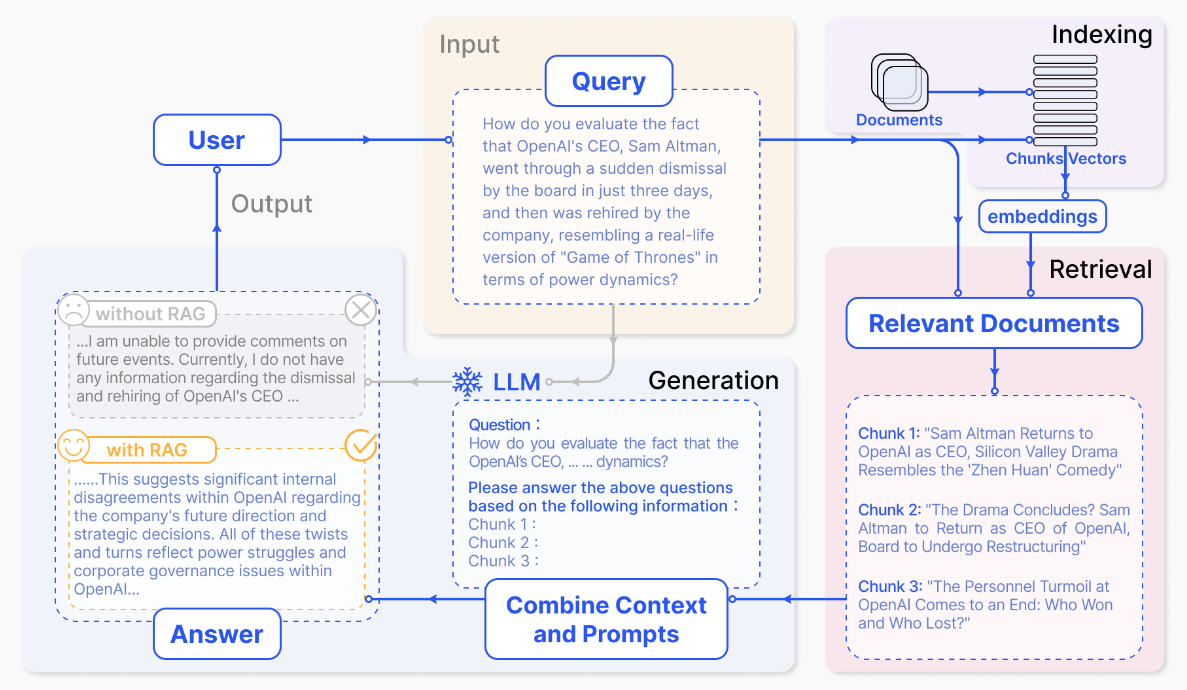

To address these challenges, researchers and developers have been exploring promising solutions. One such solution is to integrate the LLMs’ inherent knowledge with external knowledge bases during model generation process. This approach is known as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [Fig. 26.1].

Fig. 26.1 Illustration of RAG process applied to question answering. It mainly consists of basic steps. 1) Offline Indexing. Documents are collected and split into chunks, encoded into vectors, and stored in a vector database. 2) Retrieval. Retrieve the Top \(k\) relevant chunks as context or knowledge supplement. 3) Generation. The original question and the retrieved context are fed into LLM to generate the final answer. Image from [GXG+23].#

Compared to LLM’s responses that are relied on its own internal knowledge, RAG exhibits the following advantages:

Improved accuracy and reliability: By supplementing the LLM’s knowledge with current, factual information from external sources, RAG can significantly reduce hallucinations and increase the accuracy of generated content. In additional, by comparing retrieved sources and generated output, one can trace or verify claims in the output.

Improved performance on knowledge-intensive tasks: RAG excels in tasks that require specific, detailed information, such as question-answering, fact-checking, and research assistance.

Continuous and domain-specific knowledge updates: Unlike traditional LLMs, which require retraining or continuous pretraining to incorporate updated or additional information, RAG systems can be updated by simply modifying the external knowledge base. This allows for more frequent and efficient knowledge updates and the integration of specialized knowledge from particular fields or industries, making it possible to create more focused and accurate outputs for specific domains.

26.2. RAG Frameworks#

26.2.1. Basic RAG#

RAG is a technique that combines the powerful language understanding generation capabilities of LLMs with the information retrieval ability of a retrieval system/search engine. This hybrid approach aims to leverage the strengths of both systems to produce more accurate, up-to-date, and verifiable outputs.

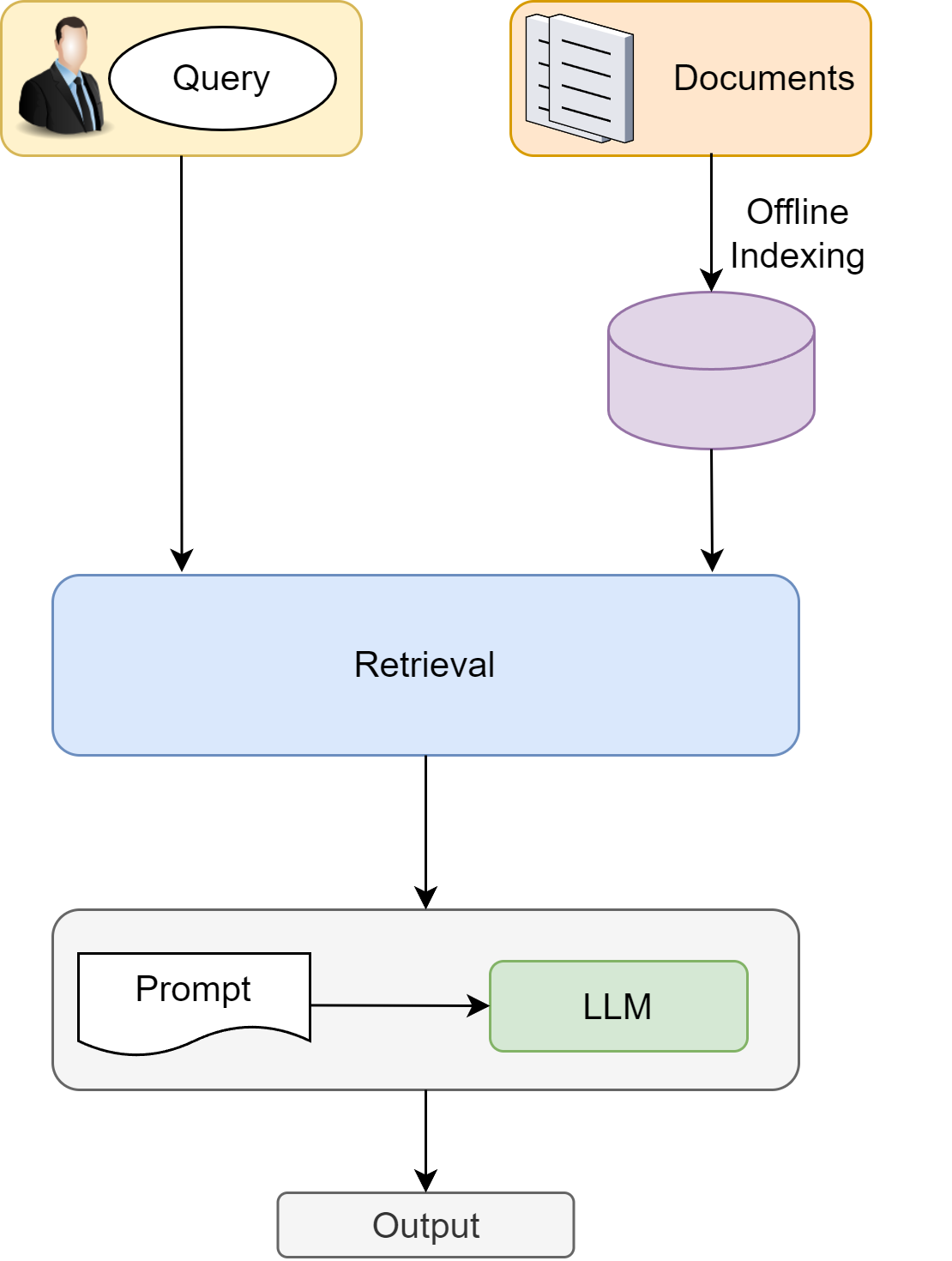

The RAG framework is built upon four fundamental components [Fig. 26.2]:

Data Collection, which involves the collection of public or private data relevant to the domain of interest. Data can come from a large variety of sources and from different modalities.

Indexing building, which transforms data source into a format that enables efficient retrieval and knowledge integration. For example, one can split a document into multiple chunks, and encode each of them into dense embedding vectors (for dense retrieval) or inverted index (for sparse retrieval). Indexing building is usually done offline.

Retrieval, which is the process of extracting relevant paragraph/chunks from the index in response to a query. This step involves online query understanding and processing - transform the query into embedding vector (for dense retrieval) or terms (for sparse retrieval) and retrieving documents using query vectors or terms.

Generation, which involves using the retrieved information along with the language model’s inherent knowledge to produce a response. This step leverages the power of large language models to understand context, integrate the retrieved information, and generate coherent and relevant text.

Fig. 26.2 Illustration of a basic RAG framework.#

Example 26.1 (A minimal RAG example)

The Vanilla RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) operates in a simplified manner as follows:

The text is divided into chunks.

These chunks are then encoded into vectors using a Transformer encoder model, and all these vectors are stored in a vector database.

Finally, a Language Model (LLM) prompt is created, and the model answers user queries based on the context retrieved from the top-k most relevant results found through vector indexing in the vector database.

During interaction, the same encoder model is used to vectorize user queries. Vector indexing is then performed to identify the top-k most relevant results from the vector database. These indexed text chunks are retrieved and provided as context to the LLM prompt for generating responses to user queries.

Example LLM prompt:

Give the answer to the user query delimited by triple backticks {query} using the information given in context delimited by triple backticks {context}. If there is no relevant information in the provided context, try to answer yourself, but tell user that you did not have any relevant context to base your answer on. Be concise and output the answer of size less than 80 tokens.

26.2.2. RAG Optimizations#

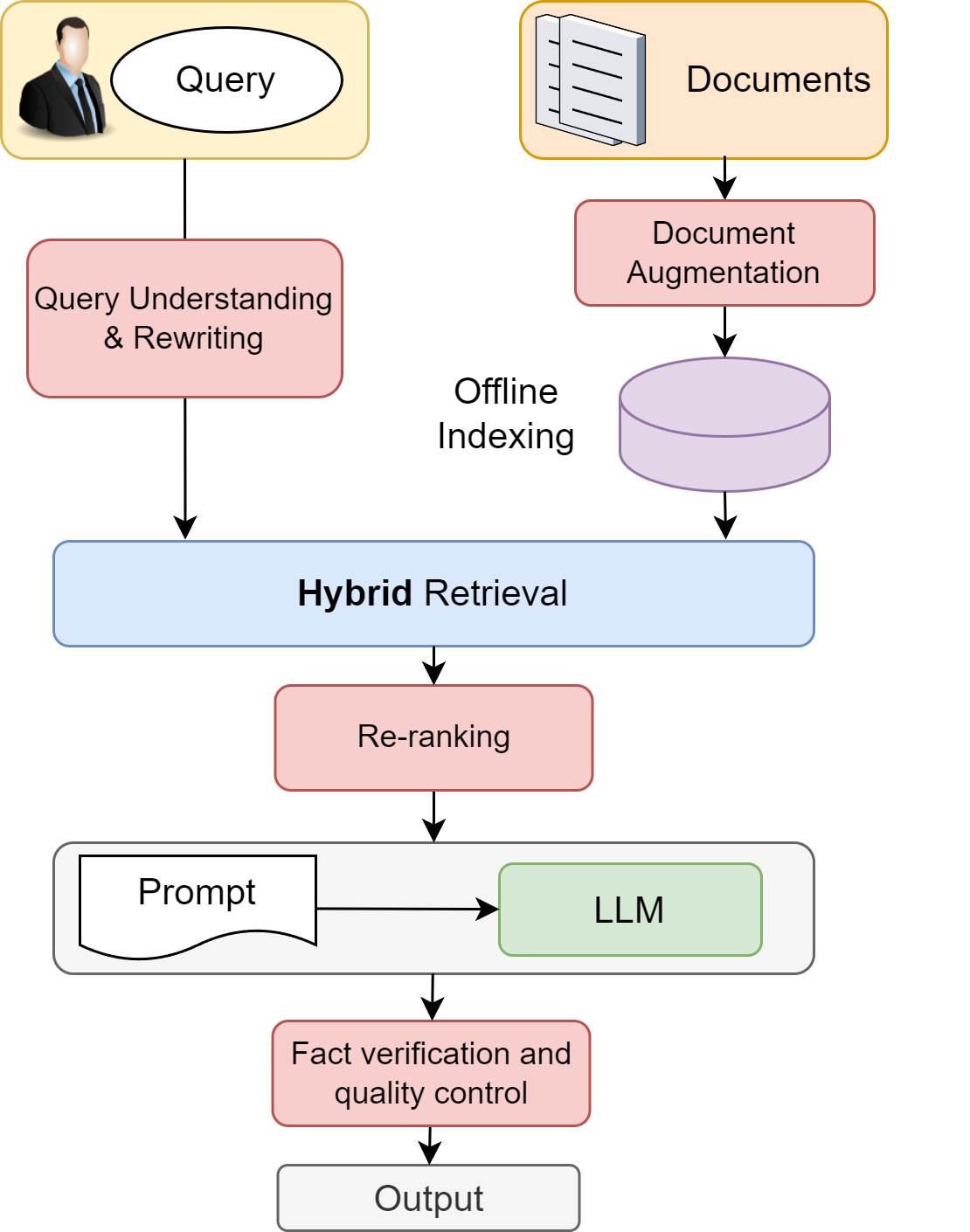

Various optimizations can be applied to the basic RAG framework [Fig. 26.2] to improve the quality and reliability of the system’s outputs. These optimizations address common challenges in RAG systems, including query-document mismatch, retrieval accuracy, and output reliability.

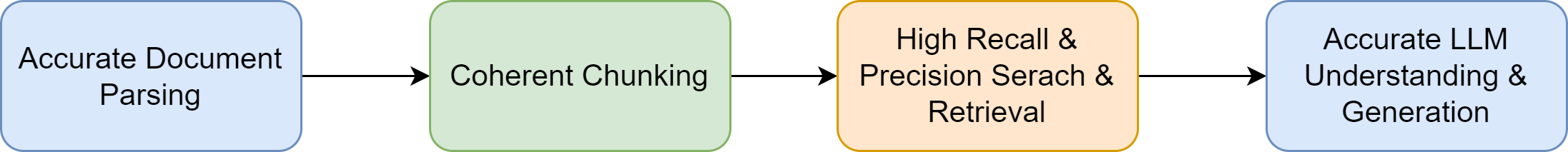

As shown in Fig. 26.3, we can divide optimizations into the following categories:

Document Understanding & Augmentation:Instead of performing mechanism chunking to split the document, we can apply language understanding models to split documents into semnatically coherent units. Besides, we can enriches documents with additional context, metadata (e.g., stamptime), and alternative representations (e.g., summaries, queries related to document) before they enter the indexing phase. This enrichment makes documents more discoverable and helps maintain their semantic context even when they are split into chunks for processing.

Query Understanding and Rewriting: This enhancement addresses one of the fundamental challenges in information retrieval: the vocabulary mismatch between query language and document language. The system can employ LLM to analyze and reformulate user queries, making them more effective for retrieval. It can help complex, multi-concept queries by decomposing the original query into multiple manageable subqueries.

Hybrid retrieval: Instead of using only sparse retrieval or dense retrieval, one can combine them together to form a hybrid retrieval system. For example, encoder models used in dense retriever can produce additional features for rankers in the sparse retriever side.

Re-ranking for quality control: After the initial retrieval, the Re-ranking step can significantly improves the quality and precision of retrieved content before it reaches the LLM. Documents are re-ranked using a much powerful model based on their contextual relevance to the user query, not just the vector semantic similarity. In addition, the re-ranking process can use extra rules to penalize similiar documents to promote a diverse set of relevant documents are sent to LLM.

LLM Understanding & Generation:Even with high-quality inputs to LLM, LLM can still produce poor results. This can be alleviated by improving model size, pretraining data quality and distribution, and fine-tuning strategies.

Output verification: As the final layer quality control, after the LLM’s output, we can add an additional step to validates the LLM’s output against the retrieved and re-ranked sources. This final check ensures accuracy and consistency.

Fig. 26.3 Optimization of the basic RAG framework in different components.#

26.2.3. RAG Challenges in Practice#

The following key factors are essential to a successful application of RAG in real-world. These four keys are sequentially dependent and any issues on one-of-them will cause response of poor quality.

Fig. 26.4 Key factors underlying a successful RAG product.#

Following table summarize practical challenges and possible causes when applying RAG into actual product.

Issue Type |

Document Understanding |

Query Understanding & Ranking Service |

LLM |

|---|---|---|---|

Hallucination |

Chunking, truncation, text extraction errors, incomplete |

Model generate hallucination |

|

Refusal to Answer |

Search results irrelevant & incomplete |

Model not understanding content |

|

Incomplete Response |

Incomplete chunking |

Search results irrelevant & incomplete |

Model summary incomplete |

Slow Response Time |

Search too slow |

Large model parameters |

26.3. RAG Evaluation#

Evaluation and benchmarking are crucial steps for RAG development. You cannot improve something you cannot measure it.

RAG application evaluation consists of two facets:

Retrieval Evaluation, which evaluates

Context relevance between the retrieved sources and the query, which can be further measured by ranking metrics like recall, precision, and nDCG.

Diversity of retrieved sources.

Response Evaluation, which evaluates if the final LLM response:

Consistence & faithfulness: Be consistent with retrieved context - if the answer is faithful to the retrieved contexts (in other words, whether if there’s hallucination).

Relevance Whether the generated answer is relevant to the query.

Correctness & usefulness Addresses the information need of the query and being useful (if the query is an information seeking query).

Other dimensions

(Expected Style) has expected style (like conciseness, clarity for summary type applications)

(Insturction following) Follows additional guidelines if any (specified by the user).

We can leverage established relevance and ranking quality metrics to evaluating the retrieval quality. For example

One can use LLM as query-document relevance labeler, and compute precision and nDCG metrics. When we adopt RAG to a new domain, we might not have enough test data to evaluate how the system works. We can leverage LLM to generate synthetic (question, answer) pairs.

Diversity of retrieved results might also play an important role in tasks that require LLM to generate complete and comprehensive results. As typical ranking metrics does not penalize duplicate results, one might need to develop alternative diversity metrics.

Evaluting the response quality is not a straight forward task and could be subjective. One cose-effective way is to use a powerful LLM (e.g. GPT-4) or text encoder model to decide the response quality from different aspects. For example,

Consistence & Faithfulness: One can use LLM to validate if claims in the generated output is consistent with the claims in the retrieved context.

Relevance: One can use text encoder to measure the semantic similarity between the query and the answer in the embedding space.

Correctness & usefulness: If one has the reference answer, one can use string matching approach like BLEU score to check if the generated answer matches that of the reference answer. Checking usefulness will be dependent on user scenarios.

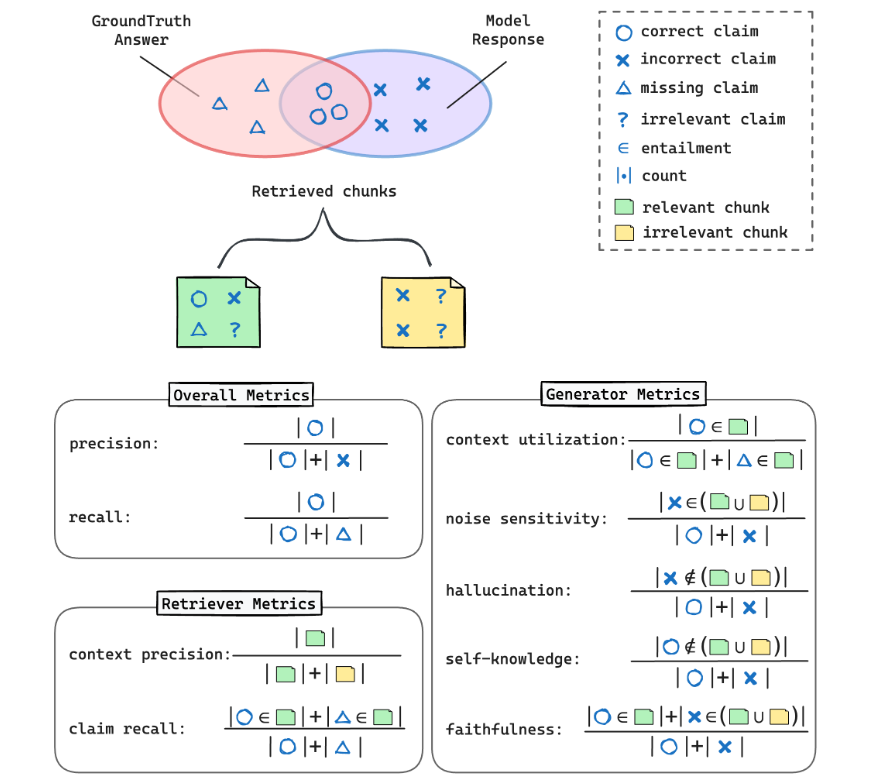

There are also efforts to automate the RAG evaluation process, as shown in the following [Fig. 26.5] from RAGChecker [RQH+24].

The key idea is to separate the overall metrics into retriever metrics and generator metrics and to compute metrics at a fine-grained chunks or claim level.

Ideally, a perfect retriever returns precisely all claims needed to generate the ground-truth answer. Therefore,

One can use precision to measure how many chunks are relevant (i.e., any ground-truth claim is in it) with respect to all retrieved chunks.

One can use claim recall to measure how many claims made in the ground-truth answer are covered by retrieved chunks.

Given retrieved chunks (possibly mixing relevant and irrelevant information), a perfect generator would identify and include all ground-truth-relevant claims and ignore any that are not. Because the generator’s results have dependency on retrieved chunks, we use the following metrics to capture different aspects of its performance.

Context utilization, which captures percentage of correct claims in the final output over the correct claims in the retrieved chunks.

Noise sensitivity, which is the percentage of incorrect claims arising from retrieved chunks over the total number of output claims. A generator with high noise tolerance is expected to have lower number of incorrect claims arsing from retrieved chunks.

Hallucination, which is the percentage of made-up, incorrect claims over the total number of output claims. The made-up claims here refers to claims not coming from retrieved chunks.

Self-knowledge, which is the percentage of correct claims not coming from retrieved chunks over the total number of output claims. This captures the ability to utilize its own knowledge.

Faithfulness, which is the percentage of claims coming from retrieved chunks over the total number of output claims. A perfectly failthful generator will have every output claims originated from retrieved chunks; In other words, its hallucination and self-knowledge metrics are zero.

Fig. 26.5 llustration of the proposed metrics in RAGChecker. Image from [RQH+24].#

26.4. Conversational IR#

26.5. RAG Optimization: Document Understanding#

26.5.1. Indexing Data Sources#

In the indexing stage, there are different data sources, and each has its benefits and challenges.

Data Type |

Examples |

Benefits |

Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

Unstructured Data |

Text, Web pages, Wikipedia, domain specific corpus |

Large availability |

Need quality control (e.g., remove bias, noisy content) during indexing time; Difficult to parse |

Semi-structured Data |

PDFs, structured markdowns, or Data that contains a combination of text, table, image information. |

Cleaner content than unstructured text and web pages |

Challenges are chunking while preserving table completeness. Converting table to text requires additional tools. |

Structured Data |

Knowledge base, knowledge graph. |

Organized, clean information |

High cost to maintain up-to-date information; Need tools to generate KG search queries; requires additional effort to build, validate, and maintain structured databases. |

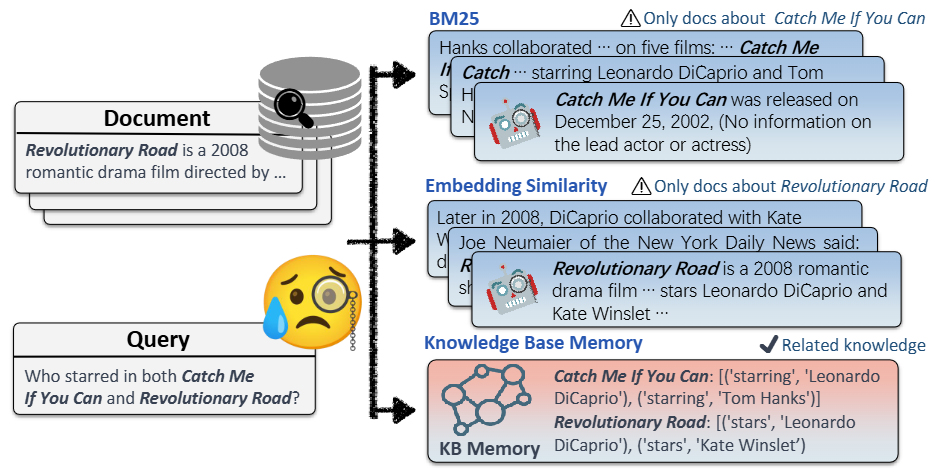

Performing search in a structured knowledge base usually involving additional preprocessing steps than performing search in unstructred/semi-structred data source [WYQ+23]. For example, to search entity in a knowledge base, we need to first extract entities from the query [Fig. 26.6].

Fig. 26.6 Comparison between retrieval results from document corpus and knowledge bases. Retrieval from knowledge base (based on key phrases extracted by LLM) could avoid concept/entity missing issue. Image from [WYQ+23].#

26.5.2. Document Parsing#

Depending on the type document sources, we need to use different tools to extract text, image, etc from the document.

For html webpage and markdown files, which use tags or specific syntax to organize texts, there are available tools to extract texts from tags like headings, body, etc.

Parsing PDFS is more challenging due to its large variation of layout and organization. For relatively simple PDF, one can use rule-based method to extract layout and structure based on pre-defined patterns. However, rule-based methods are less useful for PDFs with complex layouts.

A more advanced approach will leverage OCR (Optical Character Recognition), which treat each page as an image and extract elements from the image. It also leverage advanced LLMs (e.g., multi-modality LLM) to extract and separate distinct elements like code, image, table. There are many available online services in this line of approach.

26.5.3. Data Source Augmentation#

For unstructured data sources, it can improve document understanding and feature derivation by augmenting the data source with additional information.

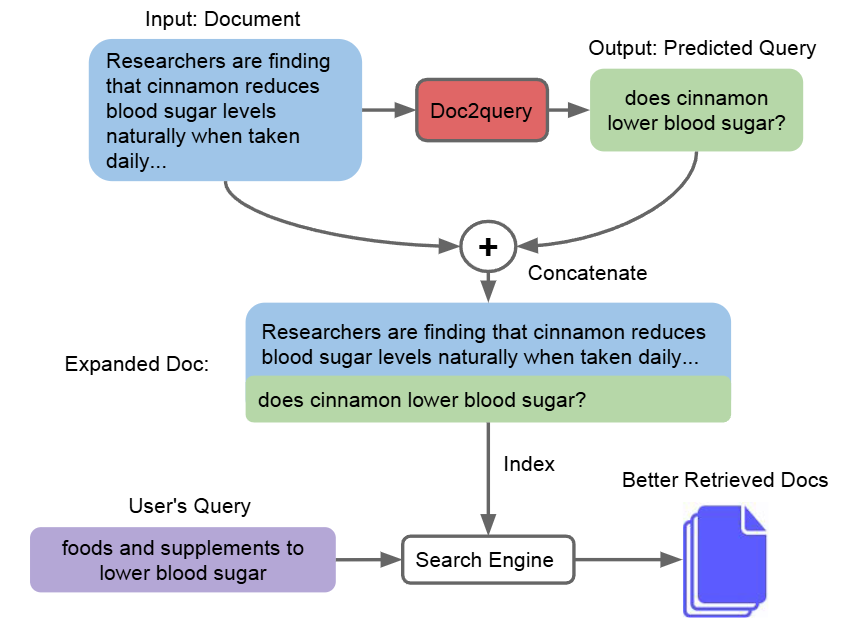

For example, chunks can be enriched with metadata information such as page number, file name, author, location, category, key entities, timestamp. Augmented data can also be artificially constructed. For example, adding summaries of paragraph, as well as introducing queries can be answered by the paragraphs (known as doc2query Fig. 26.7 [NYLC19]).Metadata are useful matching signal for retrieval stage. For example,

Location can be used to improve the retrieval results for location sensitive query.

Timestamp can be used to improve time-aware retrieval model, ensuring the fresh knowledge are ranked higher and avoiding outdated information.

Key entities in metadata can help retrieval of documents mentioning particular people, location, etc.

For multi-modality elements like tables, images, and codes, it is critical to add metatable to make them searchable. For example

Add titles and key summary for table

Add captions for images using text to image encoder-decoder models

Add code description for code snippet

A key consideration when enrish documents with the various metadata is the associated compute costs, as nowadays many metadata are extracted using LLMs. One can optimize the cost by using cheaper LLM models or only selecting critical documents for enrishment.

Fig. 26.7 Use doc2query to enhance retrieval performance. Image from [NYLC19].#

26.5.4. Document Splitting and Granularity#

During document indexing stage, we need to split documents into different chunks. The goal is to break down a full-length documents into smaller, more manageable pieces of text. This serves a few purposes:

Creating semantic units of data centered around specific information: This can make it easier to retrieve and use the data, as it is organized into smaller, more focused units.

Allowing knowledge to fit within the model’s prompt limits: If we feed a full-length document into the prompt, we would be likely to run into size limit problems.

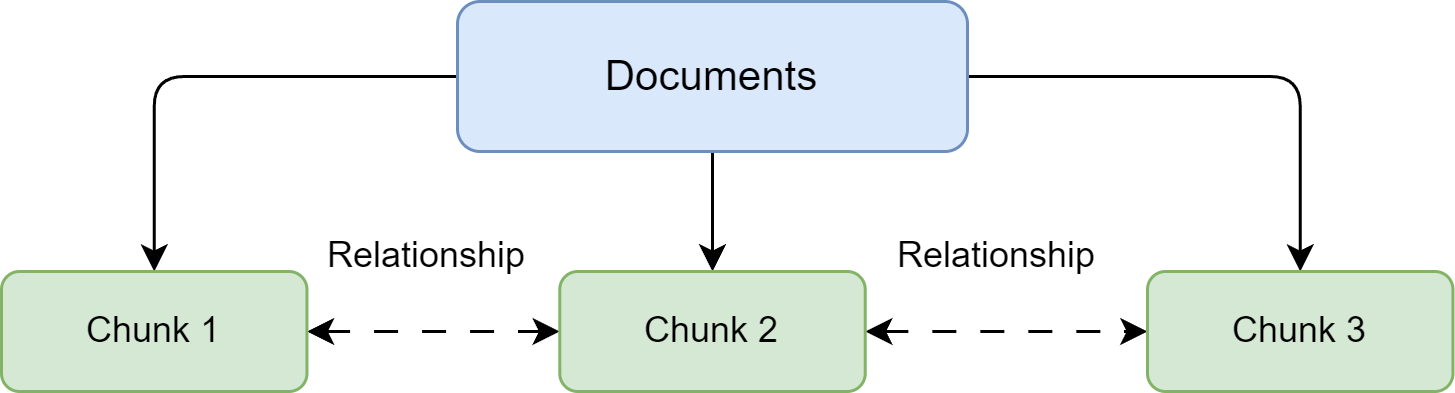

Allowing the creation of relationships between chunks: This means that chunks can be linked together based on their relationships (the relationship can be as simple as preceding or next chunks), creating a network of interconnected data. This can be useful to derive structures within the documents. See Document Chunk Relationship.

Fig. 26.8 Documents are splitted into inter-connected chunks.#

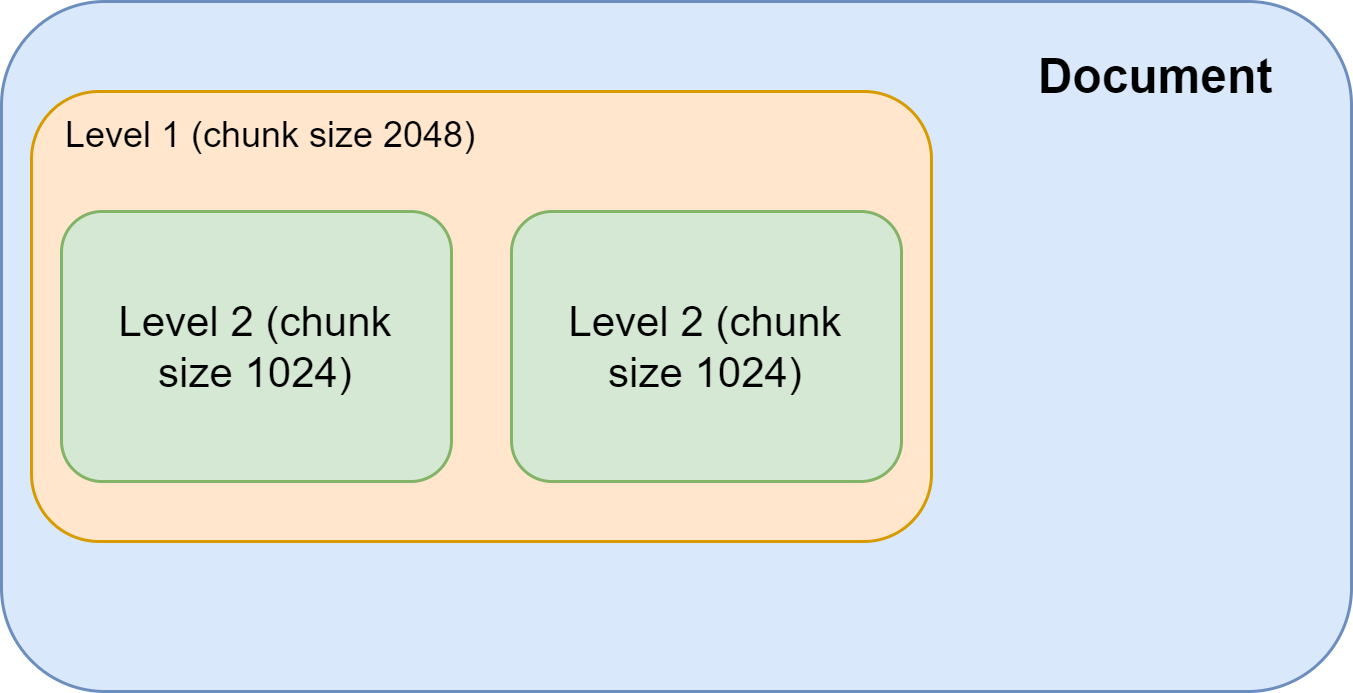

The size of chunks ranges from fine to coarse, including phrases, sentence, paragrpahs. From retrieval perspective, coarse-grained retrieval units fundamentally improve the recall at the cost of precision; that is, it can provide more relevant information for the problem, but they may also contain redundant, verbose content, which could distract the retriever and language models in downstream tasks. Intutively, encoding a large chunk of text into a single vector will have information loss, leading to poor retriever performance.

On the other hand, fine-grained retrieval unit increases the burden of retrieval - it increases the number of chunks needed for offline indexing and requires retrieving more chunks for online querying stage. Despite its higher cost, fine-grained retrieval unit does not guarantee context completeness and semantic integrity (i.e., not enough context). As a result, the quality of LLM response will be affected negatively.

From a high level, an ideal splitting should consider the following factors:

Semantic coherence: Chunks should maintain semantic coherence - split boundaries should respect natural semantic units and closely related information should stay in the same chunk.

Size consistency: Chunks should be sized appropriately for the embedding model.

Information density: Each chunk should contain sufficient information to be independently meaningful.

There are different approaches to splitting:

Mechanical splitting based on a fixed window size. This has the lowest processing cost, but there is no guaratee on maintaining semantic completeness for each chunk - it can create arbitrary breakpoints in the middle of sentences. One mitigation is to use overlapping sliding windows during splitting.

Structure-aware splitting by leveraging document structures (headers, sections). This also has low processing cost and it respect the hierachical organization of the docuemnt. However, the chunk size can vary a lot as different documents can organize differently. Also, this method can only apply to relatively formal text data with such structural annotations.

Semantic-based splitting. This method invovles using language understanding model to predict the semantic relationship between sentences and paragraphs. For example, we can use BERT to predict if two sentences are sementically close via the next sentence prediction task. Consecutive sentences and paragraphs that are closely related to each other will be grouped into the same chunk. This method is much costly compared to previously two approaches, but it preserves topic coherence within the chunk.

26.5.5. Document Chunk Relationship#

Creating relationships between chunks can be useful for several reasons:

Enables more contextual querying: By linking chunks together, you can leverage their relationships during querying to retrieve additional relevant context. For example, when querying a node, you could also return the previous or next chunk to provide more context.

Allows source tracking: Relationships encode where chunks originated and how they are connected. This is useful when you need to identify the original source of a chunk.

Enables navigation through nodes: Traversing Nodes by their relationships enables new types of queries. For example, finding the next chunk that contains some keyword. Navigation along relationships provides another dimension for searching.

Supports the construction of knowledge graphs: Chunks and relationships are the building blocks of knowledge graphs. Linking chunks into a graph structure allows for constructing knowledge graphs from text

Improves the index structure: Some more complex indexes, such as trees and graphs, utilize chunk relationships to build their internal structure. Relationships allow the construction of more complex and expressive index topologies.

In summary, relationships augment the chunk with additional contextual connections. This supports more expressive querying, source-tracking knowledge graph construction, and complex index structures.

The most basic relationship between chunks are a previous or next relationship between them. The relationship tracks the order of chunks within the original Document.

There are other types of relationships that we could define.

SOURCE: The source relationship represents the original source Document that a chunk was extracted or parsed from.

PARENT: The parent relationship indicates a hierarchical structure where the chunk with this relationship is one level higher than the associated chunk. In a tree structure, a parent chunk would have one or more children. This relationship is used to navigate or manage nested data structures where you might have a main chunk and subordinate chunks representing sections, paragraphs, or other subdivisions of the main chunk.

CHILD: This is the opposite of PARENT. Child chunk can be seen as the leaves or branches in a tree structure stemming from their parent chunk.

In this way, the different levels can be used to adjust the accuracy and depth of search results, allowing users to find information at different granularity levels.

Fig. 26.9 Documents are organized hierarchical chunks.#

26.5.6. Utilizing Knowledge Graph#

26.5.6.1. Fundamentals#

Compared with unstructed text as an external knowledge source, one can utilize knowledge graphs to represent information in a structured, interconnected format. By querying a knowledge graph, we can usually obtain concise and comprehensive results for the generator to process.

Knowledge graphs consist of entities (nodes) and relationships (edges) between those entities. Entities can represent real-world objects, concepts, or ideas, while relationships describe how those entities are connected.

During querying time, exploring these connections will allow us to find new information and make conclusions that would be hard to draw from separate pieces of information.

Example 26.2 (Knowledge graph example)

Suppose we have a collection of documents containing text chunks describing different person works for different companies.

To utilize knowledge graph in the RAG, we first use LLM to extract entities and their relationship from documents. In this case, we can extract the information on person works for company, where person and company are entities, and works for is relationship.

For an easy local query like where does Tom work?, we start with the knowledge graph node Tom, and follow the works for relationship edge to search for answer. Such local query is also straight forward for basic RAG as long as there are sentences in the original text describring Tom’s employment status.

For a global query like who works for company DeepAI, we start with the knolwedge graph node DeepAI, and follow the works for relationship edge to search for all the persons working for DeepAI. If the work for fact is scattered, and implicitly stated in different chunks, it is very challenging for basic RAG retrieve all these relevant chunks (i.e., the recall needs to be sufficiently high).

For another reasoning-needed query does Michael work for the same company as Tom, with knowledge graph, we can easily solve the query by examining nodes of Michael and Tom as well as their edges to draw conclusion.

The following table compares knowledge graph and vector databases from different aspects.

Feature |

Knowledge Graphs |

Vector Databases |

|---|---|---|

Data Representation |

Entities (nodes) and relationships (edges) between entities, forming a graph structure. |

High-dimensional vectors, each representing a chunk of text from a document. |

Retrieval Method |

Starting with nodes and traversing the graph following relationship edges |

Similarity search in high dimensional space to identify most relevant chunks |

Explainability and transparency |

Human-interpretable representation of knowledge, include graph structure and relationships between entities. |

Less interpretable to humans due to high-dimensional numerical representations. Challenging to directly understand relationships or reasoning behind retrieved information. |

Inference Time Reasoning |

Can reason over relationship among entities. Both explicit and implicit Relationship can be extracted during knowledge construction time. New knowledge can be derived from inference time |

Limited. Vector similarity may miss implicit relationships during inference time. Can identify explicit and simple relationship but not complex relationships. |

Scalability |

More cost to construct knowledge graph for new documents, which involves incoporating new entities and relationships from documents |

Minimal cost to indexing new documents |

Both knowledge graphs and vector databases have their strengths and use cases, and the choice between them depends on the specific requirements of the application. Knowledge graphs excel at representing and reasoning over small-scaled structured knowledge (e.g., representing complex relationships and enabling multi-hop reasoning), while vector databases are well-suited for large scale tasks that rely heavily on semantic similarity and simple reasoning.

26.5.6.2. Challenges#

Setting up knowledge graphs for RAG applications in the real world can be a complex task with several challenges:

Knowledge graph construction: Building a high-quality knowledge graph is a complex and time-consuming process that requires significant domain expertise and effort. Extracting entities, relationships, and facts from various data sources and integrating them into a coherent knowledge graph can be challenging, especially for large and diverse datasets. It involves understanding the domain, identifying relevant information, and structuring it in a way that accurately captures the relationships and semantics.

Data integration: RAG applications often need to integrate data from multiple heterogeneous sources, each with its own structure, format, and semantics. Ensuring data consistency, resolving entity and relationship conflicts, and mapping entities and relationships across different data sources is non-trivial. It requires careful data cleaning, transformation, and mapping to ensure that the knowledge graph accurately represents the information from various sources.

Knowledge graph maintenance and update: To ensure up-to-date RAG application, Knowledge graphs also need to be continuously updated and maintained as new knowledge becomes available or existing knowledge changes. Keeping the knowledge graph up-to-date and consistent involves monitoring changes in the data sources, identifying relevant updates, and propagating those updates to the knowledge graph while maintaining its integrity and consistency.

Scalability and performance: As the knowledge graph grows in size and complexity, ensuring efficient storage, retrieval, and querying of the graph data becomes increasingly challenging. Scalability and performance issues can arise, particularly for large-scale RAG applications with high query volumes.

26.6. RAG Optimization: Query Understanding and Rewriting#

26.6.1. Motivation#

Query understanding and rewriting is a crucial component in optimizing RAG systems. The effectiveness of RAG heavily depends on the quality of the retrieval step, which in turn relies on how well the system understands and processes user queries. Raw user queries that ** don’t directly match the way information is indexed offline** can lead to poor retrieval results.

Specifically, Key challenges that necessitate query rewriting include:

Vocabulary mismatch between user queries and stored documents, particularly for domain-specific queries containing terminology and jargon

Implicit context that needs to be made explicit

Complex queries that combine multiple concepts

Contextual understanding from multi-turn conversations

Query Type |

Example |

Rewrite Angle/Result |

Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

Vocabulary mismatch |

Why is my car not starting |

Car ignition failure diagnosis |

Document side is likely to contain words like ignition. |

Vocabulary mismatch |

Can my boss fire me for being sick |

Employment termination regulations regarding medical leave |

Document side is likely to contain termination, medical leave. |

Implicit context |

Current state tax rates |

State tax rate for CA residents in 2024 |

Incoporate time and location information into the query to improve precision. |

Complex queries |

Can I take ibuprofen with my blood pressure medication while pregnant? |

Decompose to three different subqueries on ibuprofen, blood pressure medication, and pregancy. |

|

Multi-turn conversational query |

Turn 1: “Tell me about Tesla Model 3”; Turn 2: “What about its safety features?” |

Safety features of Tesla Model 3 |

Incoporate previous context into the rewritten query |

26.6.2. Approach to Vocalbulary Mismatch#

Vocalbulary mismatch often occur in querstion-answering in high-specialized domains, like law, science, engineering, etc. The reason is that concepts are often expressed differently in document language (more formal) vs. query language (less formal). Query understanding and rewriting is essential to bridge such gap by rewriting user’s query concept to professional jargon.

Traditional techniques focus on lexical and syntactic rule-based transformations, including

Spelling correction and normalization

Stop word removal and stemming

Query expansion using WordNet or domain-specific dictionary or co-occurrence statistics

Acronym restoring using predefined mappings

Tradictional approaches are usually computationally efficient, and it is predictable and interpretable. However, it often requires significant manual effort to craft rules and update dictionary.

With the advancement of LLM, LLM can be used for more sophisticated query rewriting, as shown in the following example.

Example 26.3 (LLM prompt to query rewrite)

Prompt: Given a query What’s the state tax rate? from a user located at San Jose, US on June, 2024. Rewrite this query to help retrieve comprehensive results from search engine like Google.

This approach leverages the excellent language understanding and generation of LLM, and it can capture implicit context and semantic variations without explicit rules. However, it also has the following drawbacks.

High computational cost. LLM inference is much costly than traditional technique. One can reduce the cost by using effectively distilled SLM and by using the triggering model to decide when to invoke LLM.

Lack of knowledge for queries involving rare entity names. This is an inherent drawback of LLM, which can be addressed by using a query-rewrite oriented RAG system.

26.6.3. Approach to Complex Multi-Concept Queries#

Many user queries combine multiple concepts or requirements that need to be decomposed for effective retrieval. The query decomposition involves the following steps:

Breaking down complex queries into simpler, atomic questions

Creating multiple focused, logically-related subqueries

Example 26.4

The original query Can I take ibuprofen with my blood pressure medication while pregnant?” can be decomposed into:

Is ibuprofen safe during pregnancy?

What are the interactions between ibuprofen and blood pressure medication”

LLM is best probably the best tool to handle complex queries. To guide LLM to produce useful and desired outcome, we can apply various prompting technique, like few shot prompting and CoT [Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Prompting]. For queries involving complex reaonsing, we can use Step Back Prompting.

26.6.4. Approach to Multi-Turn Conversations#

In conversational QA scenario (e.g., a chatbot), understanding user’s query requires the understanding of previous conversational turns. In complex scenarioes, it needs the properly handling of

Resolving pronouns and references (user might use this, that, he, she to refer to entities in previous turns)

Potential conflicting aspect (user might need agree and then disagree as the conversation evolves)

Topic switches (user might switch to another topic during one conversation session)

Given the complexity of multi-turn conversations, using LLM can offer a clean solution rather than using multiple specialized NLP modules/models.

26.6.5. Advanced Query Categorization#

To better understand the RAG performance over different query types, one can further categorize queries into the following types:

Explicit fact queries: Explicit fact queries are the most basic and straightforward type, which directly request specific, known facts, with answers readily available in the provided data, requiring no additional reasoning processes. For instance, the query Who invented the telephone?, its answer, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone is directly retrieved from external data.

Implicit fact queries: Implicit fact queries are more complex than explicit ones, requiring the model to reveal hidden facts within the data. The required information might be scattered across multiple data fragments or need to be obtained through simple reasoning processes. For example, the question, Which country won the most gold medals in the 2020 Olympics? requires retrieving data on multiple countries’ gold medals and comparing them.

Interpretable rationale queries: Interpretable rationale queries further enhance the complexity of the RAG architecture, requiring not only the mastery of facts but also the ability to understand and apply domain-specific reasoning justifications closely related to the data context. These queries demand both factual knowledge and the ability to interpret domain-specific rules, often sourced from external resources and rarely encountered in the initial pre-training of general language models.

For instance, in financial auditing, language models need to follow regulatory compliance guidelines to assess whether a company’s financial statements meet standards; in technical support scenarios, they must adhere to predefined troubleshooting workflows to effectively respond to user queries. These applications require the RAG architecture to provide precise and compliant responses while generating clear, understandable reasoning process explanations.

Hidden Rationale Queries: Hidden rationale queries represent the highest level and most challenging category within the RAG task classification. These queries require AI models to infer complex, unrecorded reasoning justifications relying on patterns and outcome analysis within the data. For example, in IT operations, language models need to mine implicit knowledge from historical events resolved by cloud operations teams, identifying successful strategies and decision-making processes; in software development, they must extract guiding principles from past debugging error records.

26.7. RAG Optimization: Retriever and ReRanker#

26.7.1. Retrieval Model Enhancement#

In the basic RAG system, only a dense retrieval model based on vector embedding is used. In general, dense embeddings has good performance on recall as fundamentally it is an inexact, semantically based approach. On the other hand, sparse retrieval (e.g., inverted index plus BM25), which relies on exact tem matching, has good performance on precision, particularly for queries with low level details (e.g., specific number, year, name) and rare entities. In practice, it is beneficial to combine sparse and dense retrievers and form a hybrid retriever.

Specifically, there are several drawbacks associated with dense retriever:

Computational cost: Embedding and indexing large volumes of data can be computationally expensive and time-consuming.

More focus on recall: Dense retrieval systems can sometimes favor recall over precision.

Difficulty in encoding long documents: Dense models that encode very long content into a fixed-length vectors can run into information loss issue, where important information can be diluted or lost in the embedding process.

Logical reasoning gaps: While dense model are excellent at capturing semantic similarity, they typically lack logical reasoning capabilities. This means that they can identify documents that are semantically similar to the query but may struggle to understand context or logical relationships that require reasoning beyond this pattern matching. As a result, they may retrieve documents that are superficially related to the query but not truly relevant to the user’s intent, especially in cases where the query requires an understanding of complex relationships or nuanced reasoning.

Example 26.5 (Challenging reasoning queries for dense retriever)

Which programming languages are easier to learn than Python but more powerful for data analysis? Dense retrieval might find documents about programming language learning curves and data analysis capabilities, but struggle with the comparative reasoning needed to identify languages meeting both criteria.

Movies inspired by 1984 but with happy endings Dense retrievers would likely match the semantic similarity to “Movies inspired by 1984” well, but has difficulty to retrieve documents also meeting the happy ending condition. One reason is happy ending is rarely associated with concepts like 1984, the model is hard to identify documents with rare co-occurring concepts using simple semantic matching.

On the other hand, sparse retrieval, despite its inherent vocalbulary mismatch issue, have several advantages compared to dense retrieval:

Efficient handling of large datasets: Sparse retrieval methods, such as BM25, requiring no model and are generally much efficient at handling large datasets.

High precision: Sparse methods often provide high accuracy in scenarios where the exact matching of terms is critical. They excel at retrieving documents that contain specific keywords present in the user’s query, which is beneficial in applications where keyword specificity is essential.

Simplicity and interpretability: Sparse retrieval methods are conceptually simpler and more interpretable than dense methods. The fact that they rely on explicit keyword frequencies makes it easier to understand why certain documents are retrieved in response to a query.

Example 26.6 (sparse retrieval vs dense retrieval for legal documents)

Suppose we’ve built a system for retrieving legal documents. In this scenario, user queries would likely include precise legal terms, citations, or specific phrases found in legal texts. Let’s assume a user inputs a query such as, Article 45 of the GDPR regarding personal data transfers on the basis of an adequacy decision. This query contains specific phrases, such as Article 45 and GDPR, which are likely to be found in relevant legal documents exactly in this form.

Sparse search is likely to provide very accurate results for such a query. It will accurately locate documents that contain the specific article from the GDPR, reducing noise and irrelevant retrievals. Given that legal documents often have a structured format, with different sections and articles, sparse retrieval methods can efficiently parse through this structured data and retrieve nodes based on direct references found in the query.

Because dense retrieval methods tend to prioritize general meaning over exact term matching, they may produce less accurate results in such a specialized, keyword-specific query.

Unless trained specifically on legal texts, an embedding model used for dense retrieval might struggle to accurately interpret and match the complex legal jargon and specific citation styles used in legal queries.

Combining both sparse and dense approaches can capture different relevance features and can benefit from each other by leveraging complementary relevance information. For instance, both retrieval approaches can be used to generate initial recalled results and send to the next stage for re-ranking.

There are other ways deep model can be used to enhance sparse model. For example,

Term weight prediction: Deep model can be used to predict contextualized term weights in a query, which can help sparse retrieval model to pay more attention to important terms give the query as a context. (See Contextualized Term Importance)

Enhance sparse retrieval ranker: Sparse retrieval in practice often use much more sophositcated rankers than BM25. These ranker can benefit from query-document semantic similarity feature besides query document exact matching features.

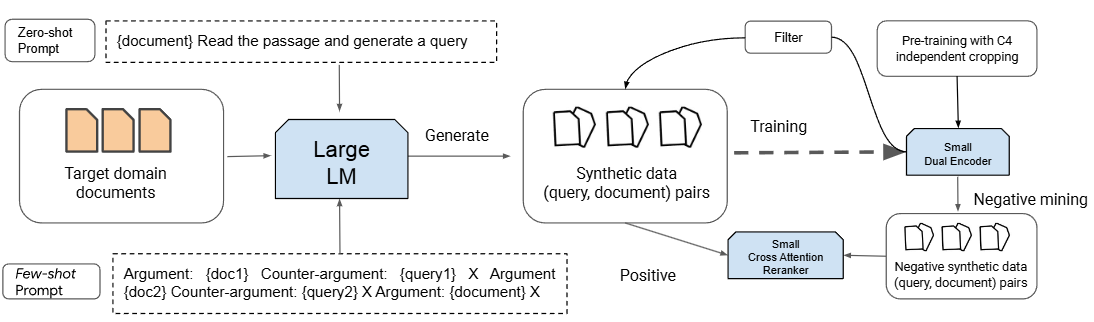

We are usually face the training data scarcity issue when we adapt a generic retrieval models to a highly specialized domain (e.g., medical, law, scientific). [DZM+22] introduces a LLM-based approach, PROMPTAGATOR, to enhance task-specific retrievers.

As shown in the Fig. 26.10, PROMPTAGATOR consists of three components:

Prompt-based query generation, a task-specific prompt will be combined with a large language model to produce queries for all documents.

Consistency filtering, which cleans the generated data based on round-trip consistency - query should be answered by the passage from which the query was generated.

Retriever training, in which a retriever will be trained using the filtered synthetic data.

Fig. 26.10 Illustration of PROMPTAGATOR, which generates synthetic data using LLM. Synthetic data, after consistency filtering, is used to train a retriever in labeled data scarcity domain. Image from [DZM+22].#

26.7.2. Retrieval Result Quality Control#

For RAG, maintaining high-quality retrieved data is crucial for generating accurate and coherent responses. Low quality content like redundancy and irrelvant will mislead LLM. In the following, we discuss several different approaches for quality control.

Reranking: Reranking is a commonly used, and effective quality control measure to improve the precision of retrieved results. Reranking can employ both rule-based methods (utilizing metrics like Diversity, Relevance, and MRR) and model-based approaches (e.g., BERT cross-encoder). The outcome of reranking is to select the most relevant and useful paragraphs for the LLM to consume.

Context Compression: A common misconception in the RAG process is the belief that retrieving as many relevant documents as possible and concatenating them to form a lengthy retrieval prompt is beneficial. However, excessive context can introduce more noise, diminishing the LLM’s perception of key information .

LLM-based quality evaluator: We can also prompt the LLM to evaluate the retrieved content before generating the final answer. This allows the LLM to filter out documents with poor relevance.

26.7.3. Diversity Optimization#

One way to reduce the redundancy of results and at the same time to preserve information-novelty and query-relevance is to use the Maximal Marginal Relevance (MMR) criterion [CG98].

MMR selects the phrase in the final keyphrases list according to a combined criterion of query relevance and novelty of information.

Given a set of already selected documents \(S\), MMR determine the next selected document \(D_i\) from the set of unselected documents \(R\backslash S\) using the following criterion

Here \(Q\) is the query, \(\operatorname{Rel}\) is the relevance scorer, and \(\operatorname{Sim}\) is the similarity scorer, \(\lambda \in [0, 1]\) set the penality strength for redundant documents.

26.8. RAG Optimization: LLM Understanding & Generation#

26.8.1. Motivation and Objective#

With retrieved context, LLM needs to utilize the context and generate desired responses to the user query. A performing RAG system requires the LLM to have the following abilities:

Generate faithful and reliable responses that are strictly grounded in the provided context

Produce robust responses when provided context has noises (e.g., some irrelevant paragraphs)

Recognize and explicitly reject queries when context is insufficient

Identify and appropriately handle harmful or inappropriate requests

Maintain consistent response quality across diverse query types

The simplest approach to tailor LLM to above needs is through prompting with desired guideline. However, often times prompting off-the-shelf LLM usually does not fully address these fundamental needs; therefore we need additional model finetuning steps to improve the LLM to better understand and utilize retrieved information, which is discussed in the following.

26.8.2. Prompting#

If we have a capable instructed LLM, prompting is a cost-effective technique to instruct LLM to behave in certain way.

Following is an example prompt that ask LLM to provide tracable answers and to reject the question if it cannot be answered.

Example 26.7

You are an AI assistant that helps users learn from the information found in the source material. Answer the query using only the sources provided below. Use bullets if the answer has multiple points. Answer ONLY with the facts listed in the list of sources below. Cite your source when you answer the question If there isn’t enough information below, say you don’t know. Do not generate answers that don’t use the sources below. Query: {query} Sources_1:{source_1} Sources_2:{source_2} Sources_3:{source_3}

26.8.3. Model Finetuning#

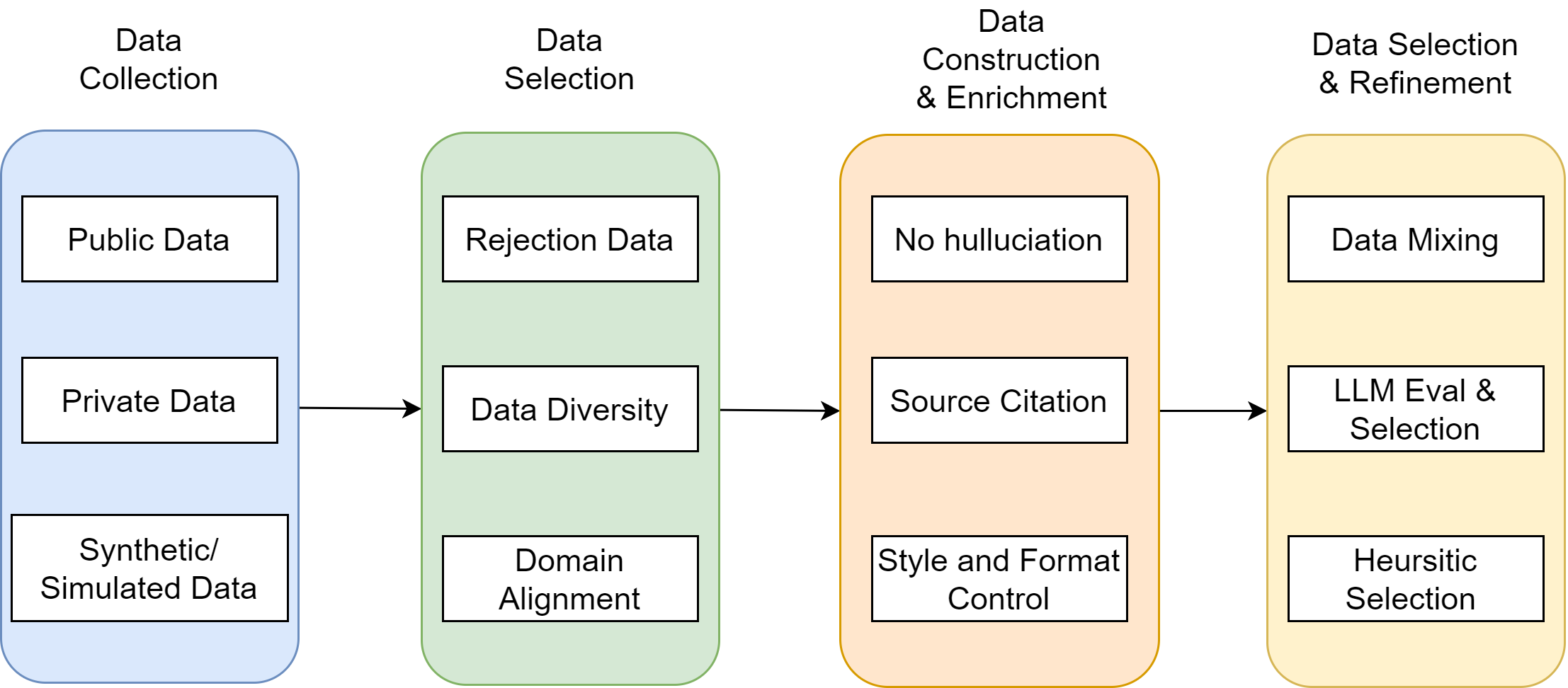

Model finetuning consists of two key steps (summarized in the ):

Training data preparation, which is a crucial step to shape the model behavior by specifying desired output and undesired output via (prompt, completion) paired data.

Training method, which invovles using SFT, DPO, PEFT, etc. See LLM Finetuning and LLM Alignement and Preference Learning.

The data preparation consists of the four key steps [Fig. 26.11]:

Data collection, in which we collect public dataset, priviate data, and use synthetic approach to generate question-context-answer.

Data selection, in which we include

Rejection samples where the LLM should learn to identify and reject queries given the context

Domain-diverse examples to ensure broad applicability

Domain-example aligning with downstream applications

Data construction and enrichment, in which

Responses with hallucination are filtered out

Source citation patterns are added

Output style and formats are adjusted to maintain consistence.

Data selection and refinement - additional data filtering and refinement steps, including balanced mixing of training data of different characteristics, quality control via LLM and heuristic rules.

Fig. 26.11 Illustration of four key steps in preparing generator fine-tuning data sources.#

Training data prepared this way ensures that the resulting model will learn to not only generates high-quality responses but also knows when and how to reject queries appropriately.

26.8.4. RAFT: Retrieval Augmented Fine Tuning#

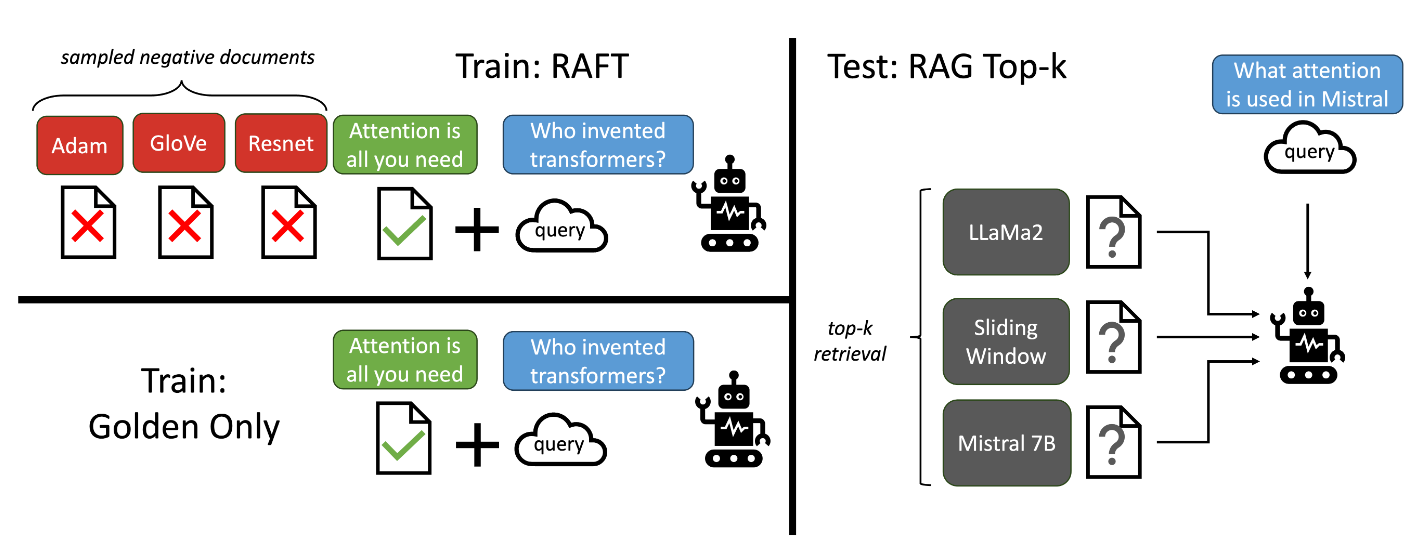

RAFT [ZPJ+24] is a fine-tuning approach aiming to enhance the LLM’s robustness to irrelevant information during a basic RAG process.

In a basic RAG process, the quality of retrieved document plays a key role in determining the output relevance and correctness of the LLM generator: Incomplete, irrelvance, or incorrect retrieved documents can lead to hallucination or non-factual statements.

RAFT addresses this issue by incoporating the imperfect retrieved sources in the generator fine-tuning process, with the objective of training the LLM to generate correct responses based on the relevant document while minimizing the negative impact from irrelevant (or distractor) document.

In RAFT Fig. 26.12, we prepare the training data such that each data point contains a question (Q), a set of documents \(\left(D_k\right)\), and a corresponding Chain-of-thought (CoT) style answer \(\left(A^*\right)\) generated from one of the document \(D^*\). We differentiate between two types of documents: golden documents \((D^*)\) i.e. the documents from which the answer to the question can be deduced, and distractor documents \(\left(D_i\right)\) that do not contain answer relevant information.

Fig. 26.12 Overview of our RAFT method. The top-left figure depicts the RAFT training approach of adapting LLMs to generate solution from a set of positive and distractor documents. Compared to training with only gold documents, RAFT will enhance model’s robustness to negative documents. At test time, all methods follow the standard RAG setting, provided with a top-k retrieved documents in the context. Image from [ZPJ+24].#

RAFT fine-tune the language model using standard supervised training based on the following mixture settings.

For \(P\) fraction of the questions in the dataset, we retain the golden document along with distractor documents.

For \((1 − P)\) fraction of the questions in the dataset, we include no golden document and only include distractor documents. The motivation is when there are only distractor documents, we are compelling the model to generate answers using its own knowledge instead of deriving them fromthe context.

Note that CoT technique is used to create a full reasoning chain, with clear cited sources. CoT technique is shown to improve model performance in RAFT.

In the test time, the model is provided with the Q and top-k documents retrieved by the RAG pipeline. Note that RAFT is independent of the retriever used.

26.9. Further RAG Discussion#

26.9.1. RAG vs Prompting and Fine Tuning#

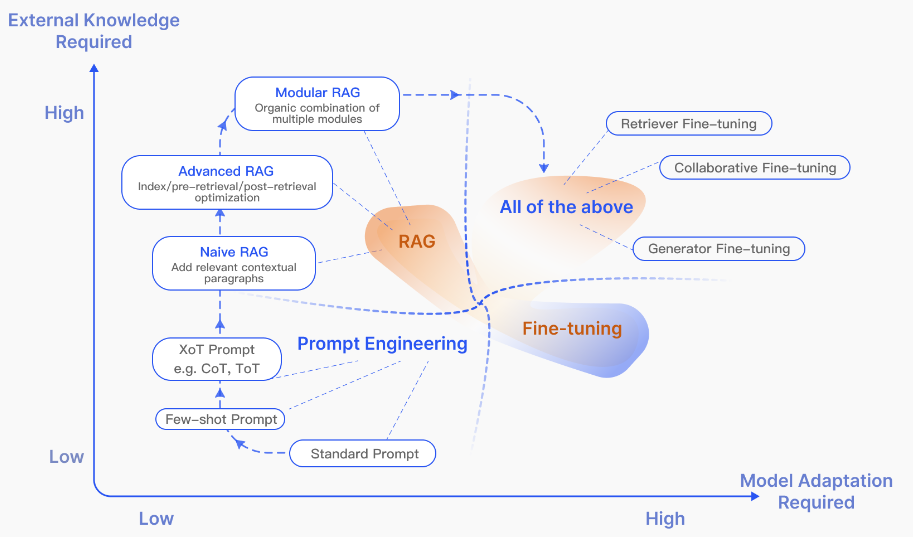

When adapt an generalist LLM to different usage scenarios, there are different approaches, including direct prompting, fine-tuning, and RAG.

Each method has distinct characteristics as illustrated in Fig. 26.13. We used a quadrant chart to illustrate the differences among three methods in two dimensions: external knowledge requirements and model adaptation requirements.

From the external knowledge requirement perspective:

Prompt engineering leverages a model’s inherent capabilities with minimum necessity for external knowledge and model adaption.

RAG can leverage external knowledge via information retrieval, making it excellet for knowledge intentsive tasks. For these tasks, indexing stage in RAG often has auto-refresh ability, enabling RAG to provide realtime knowledge updates and effective utilization of external knowledge sources with high interpretability. However, it comes with low latency scenarios, RAG has to spend extra time (~200-500ms) to perform retrieval.

FT can also be used to inject knowledge. However, the process is expensive in terms of collecting data and conducting training.

From the model adaptation perspective:

Prompt Engineering requires lowest modifications to the model. It is suitable for relative simple tasks without intensive external knowledge. However, the abiity to adapt model is limited to effectiveness of prompt engineering, which is not trivial for some tasks.

FT is suitable for customizing models to specific structures, styles, or formats. FT allows the model to generate responses to tailored to specific domains; Further, FT on speclialized labeled data can usually further enhance the model performance.

RAG enjoys the same model adaption flexibility like FT. Specifically, the retriever and generator can be both adapted to specific use cases.

Fig. 26.13 RAG compared with other model optimization methods in the aspects of External Knowledge Required and Model Adaption Required. Image from [GXG+23].#

In the following, we also summarize different factors to consider when choosing among prompting, fine-tuning, and RAG.

Factors |

Prompting |

Fine-tuning |

RAG |

|---|---|---|---|

Dynamic/up-to-date/private-sourced knowledge |

❌ |

✅ |

✅ |

Reduce hullucilation |

❌ |

❌ |

✅ |

Model behavior customization |

❌ |

✅ |

✅ |

Training cost |

❌ |

✅ |

✅ |

Explanability |

❌ |

❌ |

✅ |

General ability |

✅ |

❌ |

✅ |

Low latency |

✅ |

✅ |

❌ |

26.9.2. RAG vs Long Context LLM#

Long context LLM is one active research area, as enabling long context can open opportunties to handle more complex tasks. For example, Gemini 1.5 (https://blog.google/technology/ai/google-gemini-next-generation-model-february-2024/) has a context window of 1 million tokens. This capability makes it possible for long-document question answering, in which user can now incorporate the entire document directly into the prompt.

Do we still need information retrieval component when it comes to long context LLM? Can we just put a large document as knowledge base in the prompt? In fact, information retrieval plays an irreplaceable role. Providing LLMs with a large amount of context has the following drawbacks:

Inference speed is signficicantly reduced due to long sequences. In comparison,

The long context usually contain many irrelevant and noisy parts, which will impact the model performance.

The process is not tracable or explanable.

26.10. Bibliography#

Important resources:

Jaime Carbonell and Jade Goldstein. The use of mmr, diversity-based reranking for reordering documents and producing summaries. In Proceedings of the 21st annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, 335–336. 1998.

Zhuyun Dai, Vincent Y Zhao, Ji Ma, Yi Luan, Jianmo Ni, Jing Lu, Anton Bakalov, Kelvin Guu, Keith B Hall, and Ming-Wei Chang. Promptagator: few-shot dense retrieval from 8 examples. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.11755, 2022.

Yunfan Gao, Yun Xiong, Xinyu Gao, Kangxiang Jia, Jinliu Pan, Yuxi Bi, Yi Dai, Jiawei Sun, and Haofen Wang. Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: a survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.10997, 2023.

Rodrigo Nogueira, Wei Yang, Jimmy Lin, and Kyunghyun Cho. Document expansion by query prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.08375, 2019.

Dongyu Ru, Lin Qiu, Xiangkun Hu, Tianhang Zhang, Peng Shi, Shuaichen Chang, Jiayang Cheng, Cunxiang Wang, Shichao Sun, Huanyu Li, and others. Ragchecker: a fine-grained framework for diagnosing retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08067, 2024.